|

“sundown on chicago ave” by CGAphoto (2007). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. As you probably know, our co-founder Parker is on a road trip through the American South and Midwest. Her journey is a testament to how far we’ve come as a country—a Black woman with her white husband and mixed-race kids in an RV is, fortunately, no longer an automatic invitation for violence. However, people of color still face many challenges when it comes to travel, and not all spaces are safe, despite all the nondiscrimination laws on the books. That’s why we created Inclusive Guide and why we must continue the fight for equity and justice for all. Not too long ago—as recent as the 1970s, in fact—there existed blatantly racist areas throughout the country known as sundown towns. These all-white communities would display obvious signage telling Black travelers to stay out after sunset—or else. If Black travelers were spotted in a sundown town after dark, the community’s residents would often take extralegal measures, including verbal, psychological, and/or physical violence, to oust them. Black individuals were not only terrorized but also murdered in sundown towns. Various sundown towns existed across the South, but what some don’t know is that these racist communities could be found all around the United States. Oftentimes, there were more sundown towns in historically “free” states compared to their Southern neighbors. While some of these areas in the Midwest or West might not have labeled themselves as “sundown towns,” the fact remains that plenty of places across the country were hostile to Black individuals, even after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (And to no surprise, several of these former sundown towns remain predominantly white, sometimes upwards of 80 or 90 percent.) Moreover, sundown towns would intentionally exclude other people of color and historically marginalized groups. Prohibitions existed for not only Black individuals but also people of Chinese, Japanese, Native American, or Jewish descent, among others. Because of these discriminatory practices, traveling long distances by car was difficult for BIPOC individuals, making resources like The Negro Motorist Green Book necessary for travelers. The scary part of this history is that, well, sundown towns aren’t entirely a feature of our country’s past. These areas and attitudes persist into the 21st century but with more subtle tactics at individuals’ disposal to keep Black people out. BIPOC folks have time and again experienced discrimination in predominantly white communities—this is simply a fact. While such racism may manifest itself as a microaggression, such as an insensitive joke about Black people and culture or an uneducated comment about colorblindness, or as something more dangerous like yelling, stalking, or fighting, what ultimately ties these experiences together is a commitment to white supremacy. To unlearn white supremacy, we must know our racist past (and present). Confronting the reality of sundown towns and other deeply racist aspects of US history is only the first step, however. Educating oneself is significant, but we must also actively combat the white-supremacist systems that have been embedded within the fabric of our country. We believe that Inclusive Guide is one part of the solution, yes, but even more important is tackling policy at the highest level to ensure everybody feels safe, welcome, and celebrated no matter where they are. Whether it’s at the local coffee shop or a national park, people of all identities deserve to be comfortable being themselves. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about BIPOC travel. Sources

Coen, Ross. “Sundown Towns.” BlackPast, 23 Aug. 2020, blackpast.org/african-american-history/sundown-towns/. Accessed 1 June 2022. “Historical Database of Sundown Towns.” History and Social Justice, justice.tougaloo.edu/sundown-towns/using-the-sundown-towns-database/state-map/. Accessed 1 June 2022.

0 Comments

Among one of the darkest periods of U.S. history lies the dawn of a new morning. A dawn that the National Museum of African American History & Culture considers as “our country’s second Independence Day.” Juneteenth (short for “June Nineteenth”) was initially organized in 1866 by freedmen. It was initially known as “Jubilee Day”. This monumental event has long been a celebration in the African-American community for over 150 years and is considered one of the longest African American celebrations in U.S. History.  The Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in 1863. However, it did not free all of those who were enslaved. Contrary to what many of us have been taught, the proclamation only applied to states that were under Confederate control, not slave-holding border states or rebel areas controlled by the Union. Thus states such as Texas, the westernmost Confederate state, continued enslavement for nearly 2 and 1/2 years beyond the initial emancipation. According to History News (i.e. History Channel), enslavers outside of the Lone Star state moved to Texas, viewing it as a “safe haven” for slavery. In some cases, enslavers withheld the information until after harvest season. Although Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered two months prior, It wasn’t until over 2000 union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas where General Granger read General Orders No. 3, which stated: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” Despite the fact that freedom didn’t happen overnight for everyone, celebrations broke out among those were newly freed. Subsequently, slavery was formally abolished by the 13th Amendment in December of 1865. In 1979, Texas became the first state to make Juneteenth an official state holiday. As of June 17th, 2021, Juneteenth became a national holiday.  Regardless of Corporate America’s misrepresentations of Juneteenth, this generational celebration is testament to Black Americans’ survival against systemic degradation. A testament to our continued perseverance in a country built on Indigenous land by the bone and blood of Black people and an ode to Pan-African liberation. The social structure that supported the historical atrocities in the development of this nation are the blueprint that continue to inform systems of oppression today. This is why we created Inclusive Guide. We believe that with critical analysis of our past, together we can set clear intention for a better future. Free of systemic oppression and rooted in equity for all of us. The historical legacy of Juneteenth. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2022, June 7). Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-legacy-juneteenth#:~:text=Freedom%20finally%20came%20on%20June,newly%20freed%20people%20in%20Texas

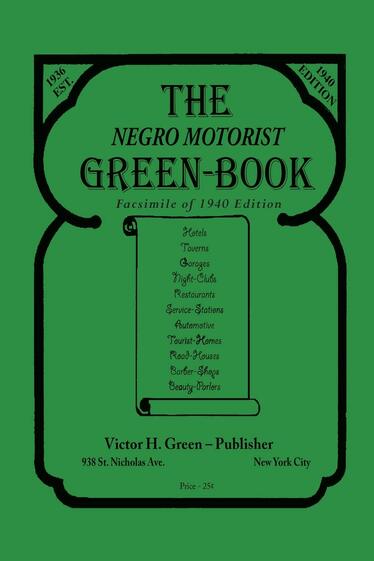

Nix, E. (2015, June 19). What is Juneteenth? History.com. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/what-is-juneteenth Parker here. I’m excited to share that this summer, my family and I are taking a two-week road trip through the American South and Midwest. We’re leaving Denver June 23 and will be driving down to Georgia and up through Michigan, all the way back to Colorado on July 10. I look forward to showing my three kids some of my favorite places and outdoor recreation areas along our path, such as Savannah and Tybee Island on the Georgia coast. While RVing across the country with your mixed-race family doesn’t seem like the most radical thing to do in 2022, safe and easy travel hasn’t always been the case for Black and brown folks. As I prepare for my family’s trip, I can’t help but think about the charged history of Black travel, including the spread of sundown towns, the Green Book, and all the other hoops people had to jump through in order to experience the “American dream” of vacations—because what isn’t more American than road-tripping.  I’ve lovingly titled my family’s journey “The Liberation Tour” because it hasn’t been that long in American history since a family like mine could safely realize this dream. Travel and outdoor recreation are historically white pastimes; not too long ago, whenever people of color wanted to participate in these activities, they needed to take extra precautions. Sundown towns—or white communities that have intentionally kept out Black people, often taking extralegal measures to terrorize and even kill those who remained past sunset—have only fell out of favor since the 1970s. To this day, there could still be unofficial sundown towns around the country, especially in communities that are mostly white. Colorado is home to more than 10 official sundown towns and over a dozen more that are “unlisted,” many of which are about an hour outside the Denver metro area, such as Burlington, Longmont, and Loveland. Within the last year, certain residents in one of the cities listed opposed measures that could have elevated the voices of its marginalized members in legislative decision-making. Many of the racist ideologies that cemented sundown towns of the midcentury still hold true today. Racism has no lane and knows no boundaries. Besides sundown towns, during Jim Crow, there were also rules of the road Black travelers needed to follow, such as pulling aside to let a white driver pass you. If you didn’t, that driver might get out of their car and physically assault you without consequence. Because every place had a different set of rules, Black travelers needed to know ahead of time where they could, say, pull over to relieve themselves or where their vehicle might be in danger of vandalism. During that time, many racist communities proudly advertised themselves as sundown towns on billboards, thereby alerting Black travelers of the perils that lay ahead, but guidelines for how to safely drive through certain areas of the country often went unstated and required insight from prior travelers to properly navigate. Unfortunately, these de facto driving guidelines still haunt us—every Black driver knows, even in 2022, just how dangerous it can be to be pulled over by a police officer. Enter The Negro Motorist Green Book. I’ve said this before, but I see my colleagues’ and my work at Inclusive Guide as taking the Green Book into the 21st century. Safety issues for travelers from marginalized communities persist to this very day. Before I discuss the need for resources like the Green Book today, I want to highlight a bit of the book’s history and why it was important. This guide was an essential tool for Black travelers in America. In fact, the inside cover of the Green Book stated, “Never Leave Home Without It.” It listed safe and welcoming spaces for Black travelers to visit between the years 1936–1966, with the ’66–’67 edition being the last issue printed, just after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. The credit for the original Green Book goes to Victor and Alma Green, alongside a Black, all-female editorial staff. Victor was a postal worker in Harlem. He asked everyone he knew to spread the word and send him postcards or letters about the safe places Black people could stay around the country. Like I mentioned earlier, many of the rules of segregated travel weren’t obviously posted. Because navigating Black travel was incredibly dangerous and unpredictable, the Green Book filled the safety gap and provided a comprehensive (yet ever-growing) list of all the safe places for Black motorists across the United States. One important Green Book site in the Denver area was Lincoln Hills. Founded in 1922 by E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt about an hour outside downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was one of the only Black resorts in the US during the 1920s. Individuals could buy 25 x 100 ft. lots at the resort, which they could then use to build summer cottages. Approximately 470 lots were sold by 1928. While the Great Depression financially prevented many Black families from realizing their summer-vacation dreams in the Colorado outdoors, lot owners still used their land as campsites or for day trips in the decades to come. You also didn’t need to own property at Lincoln Hills to take advantage of its offerings, including educational camps for Black girls and outdoor recreation activities. Plus, Black travelers were always welcome to stay at Winks Lodge, where they could eat home-cooked meals, enjoy a good cocktail, and listen to performances by talented Black musicians or writers. The passage of the Civil Rights Act may have made places like Lincoln Hills obsolete, but discrimination didn’t automatically end for travelers with one piece of legislation. Driving while Black remains a concern practically everywhere in the US. Some predominantly white communities act hostile toward travelers of color. And even if you might not be physically harmed in certain places, you’re still at risk of experiencing microaggressions and emotional or psychological abuse. The parallels between then and now are clear for people of color—the world still isn’t safe for us, nor is it safe for LGBTQ+, disabled, and other marginalized folks. Take my own family, for instance. While traveling, we’ve been stared at, questioned, and followed just for existing in certain places, especially throughout the South. Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case that banned laws prohibiting interracial marriage, may have been passed in 1967, but from my own experiences living in the world as part of a mixed-race family, I can tell you that some people still don’t like to see a white man and a Black woman together. Although I can take the heat, I don’t want my kids to experience this discrimination—and they shouldn’t have to in the first place. All this is why we need resources like Inclusive Guide to help travelers navigate the messy world of oppression. There’s a disconnect between our country’s official nondiscrimination laws and the unofficial discriminatory behavior that actually occurs. People still need to know which spaces are welcoming and which ones might be uncomfortable for them to be in, and this information can only be known through lived experience. Like the network of Black travelers that made the Green Book possible, those of us at the margins of society must share our insights and support one another. It’s time for us to reclaim travel.  Beyond using Inclusive Guide, you can join and support organizations such as The Unpopular Black and Black Girls Travel Too that seek to make travel more accessible and fun for specific groups of people traditionally left out of the American travel narrative. In these two examples, Black individuals are being centered when, for far too long, we’ve been excluded from both outdoor spaces and the general notion of “adventure.” There are too many affinity groups and resources to list here (that’s a good thing!), so I encourage you to find a group that speaks to you, but some of the organizations I support are Blackpackers, Fat Girls Hiking, Latino Outdoors, Native Women’s Wilderness, and Muslim Hikers. There’s a space for you no matter what your identity is. In the meantime, check out Inclusive Guide’s social media and blog, as well as all of KWEEN WERK’s channels, to follow me on my Liberation Tour throughout the South and Midwest. We’ll be sharing educational posts and videos related to Black travel over the course of my two-week trip. I also plan on using Inclusive Guide in real time so that you can see and learn about some of the inclusive places I visit. While this trip is ultimately a bonding experience for my family—and some well-deserved R&R for myself—I hope my journey increases the visibility of Black people in outdoor spaces and the world of travel more broadly. We be trippin’, y’all—we always have been. If you’ve been wanting to embark on an adventure but are worried that you won’t belong or that it isn’t for you, let me be the first to say that you 100%, absolutely can. Traveling is for everybody—and we’re taking it back. |