|

We at Inclusive Guide condemn Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s recent transphobic directive to investigate the families of children who have received gender-affirming care. As an organization with several gender-expansive employees, we intimately know what harm such directives and other political moves can cause to trans and non-binary individuals. If you live in Texas, we implore you to vote early to try to oust Abbott using the democratic process. We also urge Texas residents to write and call your senators and representatives, as well as support or join human rights–focused political organizations, such as the Texas Civil Rights Project and Texas offices of the Human Rights Campaign.

In 2020, The Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for queer individuals, found that 52% of all trans and non-binary people aged 13–24 in the United States seriously considered killing themselves. More specifically, a high rate of young people of color attempted to kill themselves, the highest being 31% for Indigenous youth. (The two second-highest groups were Black and multiracial young people at 21% each.) With statistics such as these, we need to do everything in our power to nurture our trans and non-binary youth, not prevent them from receiving life-saving care or resources. Abbott’s recent directive only inflames an already unacceptable situation for our country’s gender-expansive community. Additionally, research doesn’t support the misinformed idea that gender-affirming care is “child abuse.” In fact, the opposite is true: A December 2021 study in the peer-reviewed Journal of Adolescent Health asserts that gender-affirming hormone therapy is tied to lower rates of both suicidal ideation and depression in gender-expansive youth, as well as a considerable reduction in suicide attempts among trans and non-binary people younger than 18 years old. Major US medical organizations, including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Psychological Association, also support gender-affirming care models for young people. Fortunately, legal experts such as Chase Strangio of the American Civil Liberties Union say the Texas governor’s directive is not legally binding. Texas’ process for child abuse investigations remains the same, including the standard required to initiate an investigation in the first place. However, Abbott’s anti-trans posturing causes needless stress, anxiety, and fear among gender-expansive young people and their families in Texas. His use of transphobic rhetoric and symbolic political moves exploits the real lives of trans and non-binary youth as a bargaining chip for his ultra-conservative constituents. And while this directive may not be enforceable, it signals to Texans, and people throughout the country, that it’s acceptable to disregard the humanity of one our most vulnerable populations—a sentiment that does lead to consequences for the trans and non-binary community, such as transphobic bathroom bills and sports regulations. We hope you stand with us against Abbott’s cruel efforts to dehumanize our gender-expansive colleagues, friends, and family members. If you live in Texas, we implore you to vote early, join social justice campaigns, and/or contact your senators and representatives. (If you’re unsure who represents you, the Who Represents Me? tool can help you find your congressional district.) Let Abbott have a piece of us. Sources Carlisle, Madeleine. “‘It’s Creating a Witch Hunt.’ How Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s Anti-Trans Directive Hurts LGBTQ Youth.” TIME, 24 Feb. 2022, time.com/6150964/greg-abbott-trans-kids-child-abuse/. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022. Ennis, Dawn. “‘Terrible Time for Trans Youth’: New Survey Spotlights Suicide Attempts—and Hope.” Forbes, 29 May 2021, forbes.com/sites/dawnstaceyennis/2021/05/19/terrible-time-for-trans-youth-new-survey-spotlights-suicide-spike---and-hope/?sh=73724425716e. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022. Green, Amy E., et al. “Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy with Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health, in press (published online 14 Dec. 2021), pp. 1–7, doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022.

0 Comments

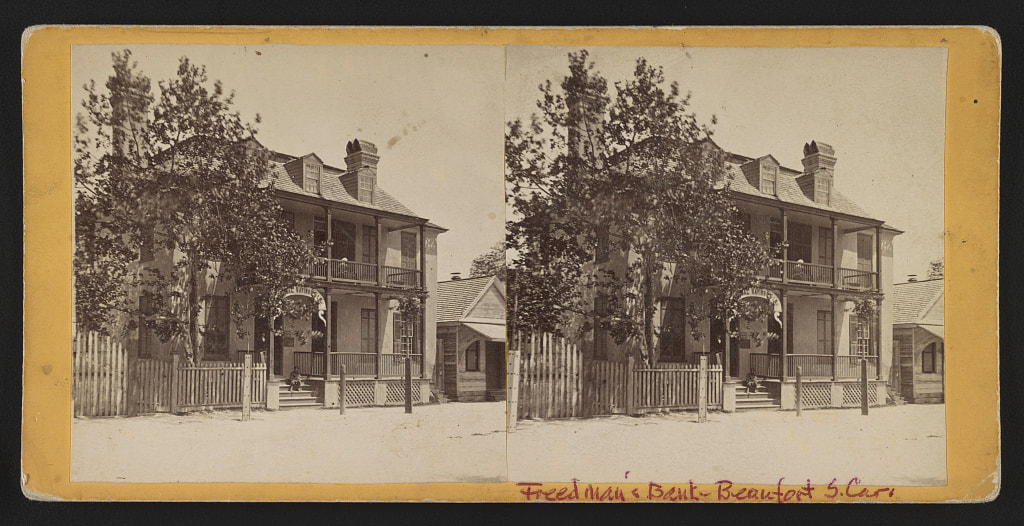

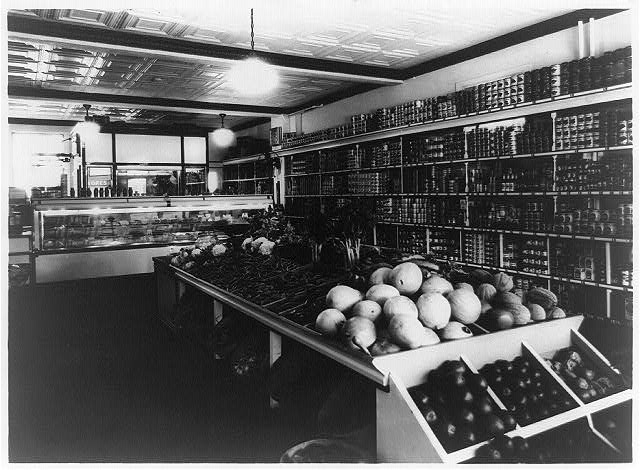

This is the fifth and final post in our “Then & Now” series for 2022’s Black History Month in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Similar to the difficulties Black individuals have faced throughout US banking history, Black-owned businesses still encounter problems of funding and overall support to this day. A good, although rough, starting point to begin tracing this problematic history lies in the aftermath of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Known informally as “Black Wall Street” for its vibrant entrepreneurial community and breadth of Black-owned businesses, the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was violently attacked on May 31 by a relentless white mob. Numerous Black residents were killed (it’s estimated between 55 and over 300), while more than a thousand homes and businesses were looted, then set ablaze. The once-thriving neighborhood and business community, which was founded in large part by the descendants of slaves, was essentially razed overnight—all because a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner tripped and accidentally grabbed a white girl’s arm in an elevator. Besides the horrific nature of the massacre being covered up by Tulsa’s white community for several decades (it wasn’t until 2000 that the tragedy was even included in Oklahoma’s public school curriculum), the Black neighborhood received little to no support from organizations and institutions in the aftermath of the destruction. Insurance companies refused to pay Black property owners’ claims for damages, while a fire ordinance was enacted to deter the community from rebuilding. Many families left to start over elsewhere, but those who did stay had to rebuild Greenwood themselves—and with opposition from Tulsa’s white community. “Rear view of truck carrying African Americans during the Tulsa, Oklahoma, massacre of 1921” by Alvin C. Krupnick Co. (1921). Public domain. This blog post doesn’t do the Tulsa Race Massacre justice, as there are many more important details about the event that deserve one’s attention. (We encourage you to learn more about the massacre by consulting the sources linked below.) We also recognize that Black businesses across America faced difficulties much earlier than 1921. However, this tragedy exemplifies the lack of support Black business owners often receive when they need it the most, a trend that haunts our country today. In 2014, for example, Los Angeles business owners Moses and Maurice Harris had to navigate an unwelcoming financial industry to jump-start their coffee shop, Bloom & Plume. Despite Moses’ background in banking and his financial know-how, as well as Maurice’s entrepreneurial experience, the brothers were rejected for a business loan by some 35 to 40 traditional banks. The number of rejections becomes even more suspect considering that Moses possessed significant collateral through home equity and both brothers boasted a steady income. Eventually, a Black-owned community bank provided the two with a loan for their coffee shop. Though the existence of such financial institutions represents a triumph for the Black business community, Black-owned companies shouldn’t be relegated to community banks for financial support. As history shows us, the burden always falls upon Black individuals to lift themselves up, but it shouldn’t be that way. The value of Black-owned businesses extends far beyond the Black community itself, offering myriad benefits to society more broadly.  “GGM_2635” by Gabriel Garcia Marengo (2018). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. As a Black-owned company, Inclusive Journeys understands firsthand how difficult it is for Black business owners to navigate the financial landscape. We hope that the Inclusive Guide, in small part, uplifts the many Black-owned businesses doing the tough work of inclusion within our communities. At the company level, we hope that the work of Inclusive Journeys proves to venture capitalists and other, more traditional sources of funding that Black-owned businesses are an asset, not a risk. If our work speaks to you, sign up for the Inclusive Guide today at inclusiveguide.com and start leaving reviews of businesses in your community. And, as always, we’d be immensely grateful if you donated to our GoFundMe campaign at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources Baboolall, David, and Earl Fitzhugh. “Black-owned businesses face an unequal path to recovery.” McKinsey Insights, 11 June 2021, mckinsey.com/featured-insights/sustainable-inclusive-growth/future-of-america/black-owned-businesses-face-an-unequal-path-to-recovery/. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. Li, Yun. “Black Wall Street was shattered 100 years ago. How the Tulsa race massacre was covered up and unearthed.” CNBC, 31 May 2021, cnbc.com/2021/05/31/black-wall-street-was-shattered-100-years-ago-how-tulsa-race-massacre-was-covered-up.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. Parshina-Kottas, Yuliya, Anjali Singhvi, Audra D. S. Burch, Troy Griggs, Mika Gröndahl, Lingdong Huang, Tim Wallace, Jeremy White, and Josh Williams. “What the Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed.” The New York Times, 24 May 2021, nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/24/us/tulsa-race-massacre.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. This is the fourth post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Throughout US history, Black individuals have experienced numerous examples of racial discrimination and general difficulties at financial institutions. This history comes into focus during the 1860s around the time slavery was abolished and Black Americans were granted citizenship (due to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, respectively). Specifically, in 1865, the US government chartered the Freedman’s Savings Bank, meant to provide Black individuals with both a safe place to deposit their income and basic financial education, services denied to them previously. Freedman’s Savings Bank started off well. Tens of thousands of Black customers collectively deposited millions of dollars into the bank, thus encouraging the financial institution to open branches across the country. But due to the volatile post–Civil War economy and mismanagement by white bank executives, who handled the Black customers’ savings riskily and inappropriately, the financial institution collapsed in 1874, leaving depositors in a precarious situation. Though the bank promised to return a portion of the savings lost to its Black customers, most individuals received either pennies on the dollar or nothing at all. “Freedman’s Bank Beaufort So. Ca.” by Hubbard & Mix (1863–1866). Public domain. The collapse of the Freedman’s Savings Bank helped promote a distrust of the financial services industry among Black Americans—and for good reason. Over the next century Black individuals would be regularly denied mortgages or auto loans, and if a credit line were successfully opened, the fees were often higher. Unfortunately, Black credit seekers experience similar examples of discrimination from financial institutions to this day. Even using a bank can be dangerous for a Black customer. Several instances of blatant racism have occurred in recent years at some of the country’s most well-known banks. At the end of 2021, Hopkins order picker Joe Morrow went to a U.S. Bank branch in Columbia Heights, Minnesota, to deposit his paycheck after a 12-hour shift at work. Despite having an account with the bank and his ID on him, Morrow was suspected by a branch bank manager of attempting to cash a fake check. The bank manager finally verified the legitimacy of Morrow’s check, but only after the 23-year-old Black man was removed by police, threatened with arrest, and placed in handcuffs. “U.S. Bank Tower Building, Lincoln, Nebraska” by Tony Webster (2018). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. In another example from 2018, Clarice Middleton tried to cash a $200 check at a Wells Fargo branch in Atlanta, Georgia, but three of the bank’s employees accused her of fraud and called the police. In that moment, Middleton thought, “I don’t want to die.” Although the police officer left without taking action and Middleton was eventually able to cash her check, the emotional and psychological scars remain. To make matters worse, after the incident, a Wells Fargo spokesperson claimed that Middleton started to shout “abusive and profane language” (she didn’t), effectively gaslighting her. The history of Black banking in America is a reminder that many basic services, such as access to a savings account, remain difficult for customers of color who continue to be racially profiled and treated disrespectfully by employees. At Inclusive Journeys, we condemn this discriminatory behavior and aim to cultivate a safer banking environment for Black and brown individuals. We encourage users to leave reviews of their experiences at banks, whether positive or negative, on the Inclusive Guide so that marginalized customers may know which financial institutions are safe for them to visit—and those which may not be. We also want to uplift the Black-owned banks that strive to make the financial services industry more welcoming and accessible to customers of color. Help us foster a better banking culture for Black and brown individuals. You can join our fight for justice by leaving a review on inclusiveguide.com and donating to our GoFundMe campaign at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources Flitter, Emily. “‘Banking While Black’: How Cashing a Check Can Be a Minefield.” The New York Times, 18 June 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/18/business/banks-black-customers-racism.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. “The Freedman’s Savings Bank: Good Intentions Were Not Enough; A Noble Experiment Goes Awry.” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, occ.treas.gov/about/who-we-are/history/1863-1865/1863-1865-freedmans-savings-bank.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. Rasmussen, Eric. “‘Banking While Black’: Police video shows how cashing a paycheck led to handcuffs.” 5 Eyewitness News (KSTP-TV), 7 Dec. 2021, kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/banking-while-black-police-video-shows-how-cashing-a-paycheck-led-to-handcuffs/. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. Williams, Mariette. “After years of banks overcharging and undervaluing Black customers, ‘banking Black’ is gaining popularity as an effective way to fight systemic racism.” Business Insider, 22 Feb. 2021, businessinsider.com/personal-finance/banking-black-americans-switching-banks-2021-2. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. This is the third post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Then & Now: Supermarket Redlining While both retail and dining racism offer a clear history of segregation, discrimination, and injustice, the story of American grocery stores isn’t as black and white. A look at the past 60 years of the country’s shifting supermarket landscape reveals a set of insidious maneuvers that has, ultimately, perpetuated a racial divide in the US. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s led to many positive policy changes and helped foster a racial consciousness across America, but self-service supermarkets and chain stores viewed the situation differently. Their white customers were fleeing cities in favor of the suburbs where racial unrest didn’t appear as pronounced. Grocers could stay in the city, but at what cost? Seeing an opportunity to earn more profits, grocery stores followed their white customers to the ostensibly “safer” suburbs where they could open larger stores with bigger parking lots, wider aisles, and more food, all on inexpensive suburban land.

Detroit serves as a prime example of this divide. In 2020, the city only had three large supermarkets: a Whole Foods and two Meijer stores. Earlier, during the mid-aughts, Detroit didn’t have a single major grocery chain. This reality becomes even more concerning when considering the city’s population breakdown: 78% of Detroit residents are Black. There’s a clear connection between the white flight from the city and the lack of big supermarkets, especially when just outside Detroit there are several Kroger stores in a ring around the border. As Detroit Food Policy Council Executive Director Winona Bynum says, “Big chains don’t see Detroit as a place where they can make money. The perception is that Detroit is a big pit of poverty and Black people will steal you blind and try to get things for a nickel.”

On top of the problematic white flight of supermarkets, many Black people continue to report discrimination and racial profiling at grocery stores, including, among other examples, being followed while shopping, directed to the sales section, or outright ignored. Not only must urban customers of color travel farther to access more affordable groceries; they also become targets of discrimination when entering grocery store chains in predominantly white suburban areas.

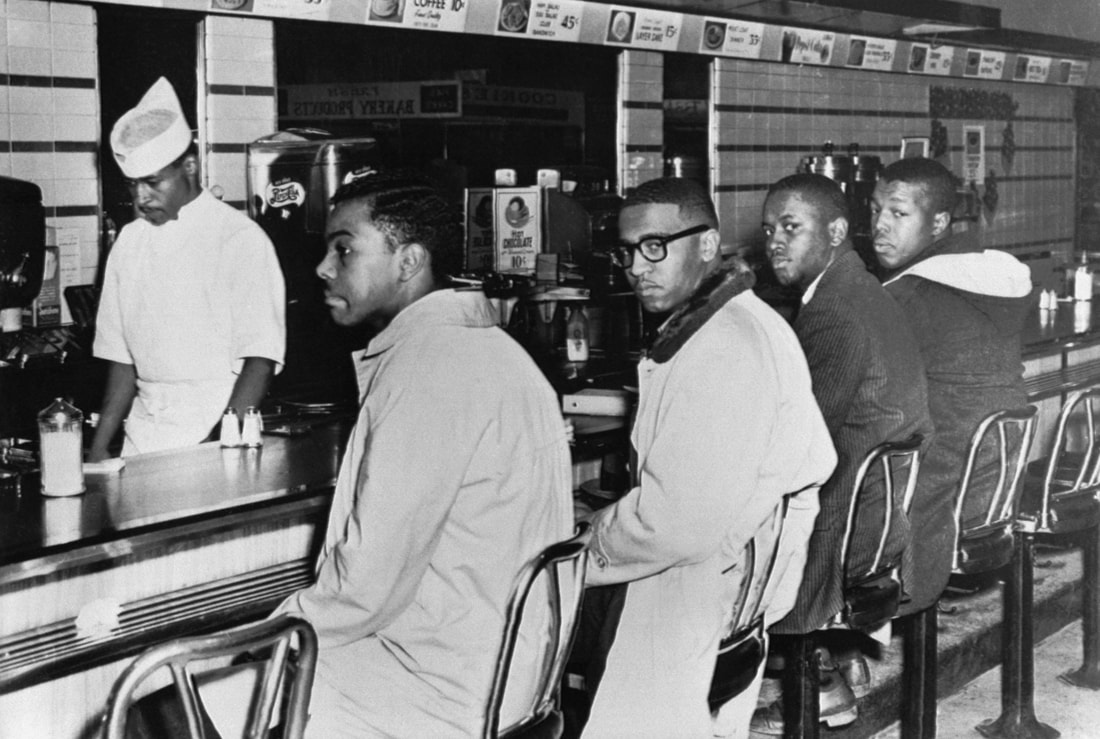

The history of supermarket redlining demonstrates why it’s more important than ever for us to support Black-owned grocery stores. One way to do this is by leaving a review of your favorite community supermarket on Inclusive Guide so that other customers of color will know it’s safe and welcoming. Conversely, you can use the Inclusive Guide to share any acts of discrimination or racial profiling you’ve experienced at a large grocery chain, thereby signaling to others that this store might not be a safe space for them. And, as the Inclusive Journeys team seeks to do with all businesses, we want to help by offering resources and training should a grocery store receive a low inclusivity rating. Help us cultivate a safer supermarket experience for shoppers of all identities. The first step is leaving a review on inclusiveguide.com. Sources Meyersohn, Nathaniel. “How the rise of supermarkets left out black America.” CNN Business, 16 June 2020, cnn.com/2020/06/16/business/grocery-stores-access-race-inequality/index.html. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. Perkins, Tom. “Why Are There So Few Black-Owned Grocery Stores?” Civil Eats, 8 Jan. 2018, civileats.com/2018/01/08/why-are-there-so-few-black-owned-grocery-stores/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. Robison, Daniel. “Racial profiling by retailers creates an unwelcome climate for black shoppers, study shows.” The Daily, 16 Nov. 2017, thedaily.case.edu/racial-profiling-retailers-creates-unwelcome-climate-black-shoppers-study-shows/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. This is the second post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives–to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Then & Now: Dining Racism In addition to retail racism, Black patrons have specifically faced discrimination in dining situations, including at restaurants, coffee shops, and other establishments. Some of the earliest demonstrations during the Civil Rights Movement took place at lunch counters at popular chain stores. A famous example began on February 1, 1960, at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth, a former general-merchandise chain with stores across America. Four Black men studying at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NCA&T)—Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond—sat down at Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter and ordered coffee and donuts but were refused service. While they expected to be arrested, the four students were, for the most part, left alone and stayed until the store closed. The following day, Blair, McCain, McNeil, and Richmond were joined by other protesters; this second sit-in was covered by the local newspaper and television station. On February 3, the demonstration grew, with more than 60 students taking turns occupying every seat at Woolworth’s lunch counter. The momentum continued into February 4 and reached close to 300 protesters, including women and white students. This series of sit-ins at the Greensboro Woolworth jump-started a number of demonstrations to combat segregation, such as picket lines, boycotts, and other sit-ins. The Ku Klux Klan eventually became involved with the Woolworth sit-in and harassed protesters in hopes of deterring them. However, the demonstration only grew stronger, as the NCA&T football team joined the effort, as well as organizers for the Congress of Racial Equality, who helped train the students in tactics of nonviolent resistance. Several months later, Woolworth and other chains agreed to serve all customers at their lunch counters, marking one of the first major successes in desegregation (other than the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case a few years prior, which desegregated public schools). Much like retail racism, though, insidious forms of racial discrimination persist to this day at dining establishments. In 2019, for instance, Black Starbucks customer Lorne Green was targeted the moment he walked into the Brandon, Florida, coffee shop and went to the restroom. Starbucks staff incessantly knocked on the restroom door, asking if he needed the help of “fire rescue,” at which point he called the company’s corporate line and reported the incident. Uncomfortable, Green eventually left the Starbucks, but not without being issued a trespassing ticket from deputies called to the coffee shop. Although Green was able to team up with an attorney to try to have the citation dropped, this incident represents racial profiling at its worst. Moreover, Green’s case resembles an incident in 2018 during which two Black men, Rashon Nelson and Donte Robinson, were arrested after asking to use the restroom at a Philadelphia Starbucks.

These examples highlight the continuing fight for racial justice, even at businesses like Starbucks that claim to have a “zero-tolerance policy” for discrimination. That’s why the Inclusive Guide is necessary—to help users navigate coffee shops and restaurants, among other businesses, safely and comfortably. On the business side, Inclusive Journeys plans to offer diversity, equity, and inclusion training and resources to companies, whether they be coffee giant Starbucks or a local business, so that their employees can help cultivate an inclusive environment for patrons of all identities. Join us as we strive to stop racism at coffee shops, restaurants, and other dining establishments. Sign up to review businesses at inclusiveguide.com, and consider donating to our project at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources “2 Philadelphia men in Starbucks controversy speak out.” FOX 13 Tampa Bay, 19 April 2018, fox13news.com/news/2-philadelphia-men-in-starbucks-controversy-speak-out. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. “Civil Rights Movement History 1960.” Civil Rights Movement Archive, crmvet.org/tim/timhis60.htm#1960greensboro. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. “Man says he was kicked out of Brandon Starbucks because he’s black.” FOX 13 Tampa Bay, 9 May 2019, fox13news.com/news/man-says-he-was-kicked-out-of-brandon-starbucks-because-hes-black. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. |