|

If you think about the word “nature,” you might conjure images of wilderness areas—the undeveloped stretches of valleys and mountains that exist across the American West, for example. More specifically, you might picture Yellowstone National Park or the famous black-and-white photos of trees, lakes, and cliffs taken by American photographer Ansel Adams. All these mental images certainly are natural, but they only represent a fraction of what nature is. As Emma Marris says in her 2016 TED Talk titled “Nature is everywhere — we just need to learn to see it” in Banff, Alberta, “Nature is anywhere where life thrives.” We at Inclusive Guide wholeheartedly agree with this more expansive definition. Romantic ideas of a pure, untouched nature discourage those within historically disenfranchised communities from connecting with the natural world. When we consider nature solely as the faraway trails, forests, rivers, and slopes that reaffirm our culture’s dominant view of the outdoors, we ultimately exclude the folks who can’t take time off to roadtrip to a national park, who can’t afford x gear or y equipment, or who are made to feel unwelcome and unsafe in certain natural environments. It’s no secret that there’s a “nature gap”—also called the “adventure gap”—in outdoor recreation, as the majority of Americans who enjoy these recreational activities are white. Indeed, Census Bureau data shows us that “[w]hite Americans vastly outnumber people of color in outdoor activities like fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching.” This is a problem. How can we fix the nature gap? The first step is redefining our relationship with the natural world. Following Marris’ lead, we must embrace the idea of nature being all around us—and yes, this includes cities and other heavily industrialized spaces. These places are natural because life, including humans but also various plants, insects, and other species, thrive in them. What about the children who live in inner-city New York, Chicago, or Philadelphia who don’t have ready access to mountaintops or waterfalls? Do they not get to enjoy nature? When a kid finds a roly poly under a rock in their front yard, isn’t that engaging with nature?

0 Comments

Parker here. Most of you know me as the co-founder of Inclusive Journeys, the company behind the user review platform Inclusive Guide. I also founded Ecoinclusive, a service that provides diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training and resources to leadership teams at environmental organizations. I’ve spent the past 24 years of my life working in natural resources, environmental education, and outdoor recreation. It’s become my life’s mission to dismantle and reimagine the systems that continue to harm historically disenfranchised individuals, especially in environmental and conservation spaces. And I won’t stop until the world’s a better place for all.

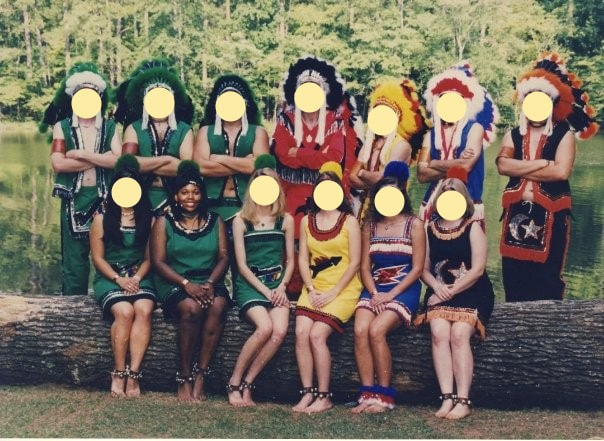

If you know me or have worked with me over the years, some of the stories in this blog post may be uncomfortable or surprising for you, but I’m sharing my experiences to bring light to the fact that there’s much more work to be done. The amount of racism and microaggressions I’ve endured over the course of my career would be truly staggering to some. This admission may also come as a surprise because in some ways, I helped to reinforce and uphold the white supremacist systems I, myself, was a victim of. This article is not a call-out but rather a reflection of my personal growth. You see, there were many times I sheepishly laughed at racist jokes about myself. There were many times I reassured those who perpetrated racism against me that I was okay and didn’t take offense. There were many times I told other people of color that things weren’t so bad. I look back at that version of myself and feel a strange mix of emotions—yes, shame and embarrassment, but also pride and hope because I’ve come so far. Because of my experiences as a Black woman, I’m intimately aware of the harsh realities those at the margins of our society are forced to endure, even when people think racism and sexism are done, ableism is fake, or the fight for queer rights is over. I’ve lost count of the number of times my mixed-race family has been harassed in public, the times I’ve been told that Black people don’t hike or camp, or the times my hair has been policed at the workplace. Though I can’t overlook the “-isms” and systems that harm me and other marginalized communities, it took me a long time to realize the presence of such structural problems in the first place. White supremacy is what the US was founded upon, and people of color are often the recipients of its torment. However, in my past, I subscribed to white supremacist delusion without even knowing it. Even as the target of white supremacist practices, I also upheld this delusion. Nobody is born “woke,” and I—like everyone on this journey—am still in the process of unlearning some of the problematic behaviors our white supremacist society encourages people to engage in. I’m not perfect, but I’ve come a long way. I want you to know that you can change, too, no matter where you’re from or what your background is. This is why I’m sharing my journey with you. A good place to start is around the ages of 18 to 20, when I began my career. In 1997, the first summer camp I worked at as a full-time counselor had a Native American theme. Campers were divided into different tribes: Shawnee, Cherokee, or Muskogee. Throughout the week, children would compete in activities to try to win the coveted “tribal shield,” which was a chest full of pins. The camp’s talent show was held in an auditorium described as the “air-conditioned tepee,” and every week counselors would perform a fake Native American love story during a ceremony called “The Pageant.” I participated, even wearing a feathered headpiece designed for female counselors while the male counselors wore headdresses. I still think about the children I worked with and the harmful stereotypes I helped perpetuate among them. During this time in my life, I was woefully unaware of the previous and ongoing genocide against Native American populations in the US. The camp’s activities not only gave campers an inaccurate representation of Indigenous life and customs; they also helped perpetuate the idea of the “extinct Native American.” These stereotypes disrespect, degrade, mock, and harm Native peoples—in fact, Indigenous individuals experience the highest rate of police killings compared to any other group. I was only able to learn all this in retrospect. Fast-forward to my early 20s. I was now working at an environmental education center in the Midwest. That center had an evening event known as the “Underground Railroad Activity.” You can probably guess what this “game” included, but I’ll expand. Students would pretend to be slaves in a traveling choir accompanying their master. This master, who was a teacher or chaperone leader, carried papers supposedly attesting to the slaves’ right to travel. Throughout the activity, the students would be stopped by various people and were instructed to look down whenever they encountered others and to be silent unless they were spoken to. Students who didn’t follow these instructions were yelled at until they submitted. During this activity I often played the role of another slave who would help the students escape, having to hide at times to avoid being caught. Toward the end of the activity, a lantern would be lit and a quilt hung to signal that the students could enter a safehouse and go downstairs to a basement, where they would wait in a dark room while the local “police” visited the house looking for escaped slaves. The folks upstairs would yell that they knew slaves were hiding in the house, threatening to find them and take them back. This horrific activity concluded with a short discussion that lacked any semblance of depth or nuance. By participating, I was complicit in how this abhorrent activity impacted both the students and myself. That center’s education staff had little background knowledge on the history of the Underground Railroad, let alone slavery, but we facilitated the activity anyway. Further, the historical “context” we provided after the game did little to justify the trauma we inflicted upon our students. It took me years to understand the psychological and emotional impact my participation had on students, as well as on myself. Several years later, I began working at a different environmental education organization. By this point, I’d vowed to myself that I’d never contribute to something like the fake Native American camp or Underground Railroad activity ever again. However, I found myself being challenged in a different way. The director of this new organization would bring her dog to work. The dog noticeably only barked at Black people. As such, she sometimes referred to her pet as her “little KKK dog.” In an effort to explain this behavior, the director said her dog had a “bad experience” with a Black person. One of my colleagues, a Black man from Philadelphia, eventually approached me about the director’s reference. I shrugged and told him that it was okay. “It’s just the South,” I added. In a moment when I should have supported my Black colleague, I excused the director’s actions, minimizing both our experiences. I thought, in a way, that I was “protecting” my colleague. The director’s behavior was reprehensible on many levels, but I was worried about the ramifications of calling out this behavior in a public way. By shrugging off my colleague’s concern, I was actually protecting the director instead. I was protecting her racist, white supremacist ideologies and practices. Although I was aware of these micro/macroaggressions, I still didn’t address them. From housing and infrastructure to education and policymaking, white supremacy is woven into every part of our society. In order to break free of white supremacist delusion, we must first be willing to wake up from it. We have to educate ourselves by reading the literature of civil rights leaders, activists, First Nations, and Indigenous peoples who are skimmed over in our history books. We must seek out intentional affinity groups such as student alliances and nonprofit organizations to build community. Education and community are the foundation upon which one can overcome the internal barriers and fear that often keep us from confronting systemic oppression. This is where my liberation lies, and it continues to set me free every day. Still, education and allyship are only one part of the solution. While remembering our past wrongs is important, it’s also important that we answer these wrongs with vigorous action and change. As a co-founder of an inclusivity-focused business, I do everything I can to empower the marginalized groups I overlooked when I was younger. For example, I invite (and compensate) Native individuals to have a voice at events that I host and to provide invaluable insights about the work I’m doing—and should be doing. I also steer folks in the direction of organizations that are doing similar work and let them know how they can directly support these causes. If you’re a leader, or have any semblance of power in our white supremacist country, you can act now to elevate the perspectives disregarded in key business decisions. We can’t dismantle the systems that continue to harm us if those at the margins of our society have no seat at the table. The reality is that I was both the victim and the perpetrator of white supremacist delusion. Everyone is affected by white supremacy, including white people—regardless of the supposed benefit. Nobody’s perfect. As such, we’re all capable of growth and change. Acknowledging our past transgressions is the first step. This healing is the very reason we created the Inclusive Guide. Everyone is part of the problem, so everyone must be part of the solution. I welcome you to join me on this journey. |