|

Similar to fashion, hair is one of the most important forms of self-expression. People wear their hair in many different ways, from short and kinky to long and straightened. Individuals may dye their hair, wear wigs, or place bows, combs, or other objects atop their heads. The breadth of hairstyles is reflective of the diversity of the human race.

Thankfully, the CROWN Act recently passed the House of Representatives and will soon be reviewed in the Senate. For those unfamiliar, the CROWN Act, short for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair, was first introduced in 2019. This congressional bill seeks to ban workplace-related prejudice and discrimination regarding race-based hairstyles, such as protective locs and braids. Hair discrimination is real and disproportionately affects Black individuals; indeed, according to the 2019 Dove Crown Research Study, Black women are 1.5 times more likely to be sent home from work because of their hair. The CROWN Act is an important step in allowing everybody, especially Black women, to feel welcome and safe regardless of the hairstyle they don. While significant progress has been made at the legislative level to combat hair discrimination and help make the US a more welcoming place for all hairstyles, there are several steps businesses, particularly salons, can take to better cultivate an atmosphere of inclusion. The following informal guide outlines a few of the ways salons may work toward inclusivity in their business practices. Hire stylists who have experience with Black hair. Walk into your neighborhood Great Clips or Supercuts, and you’re unlikely to find somebody who can style Black hair—at least not well. This isn’t so much a problem with individual businesses as it is with the cosmetology industry in America, as many beauty school students never gain experience styling Black hair. This trend effectively enables white-staffed salons to deny service to Black customers due to their hair being “too difficult to style.” Many Black women have, unfortunately, been refused service at high-end salons because of their natural hair. The easiest way for a business to address this racist trend? Hire stylists who can work with Black hair! The burden shouldn’t be on the customer to search out who can style Black hair and who can’t. Ideally, Black customers should be able to visit any salon without doubts or fear that their hair won’t be taken seriously. Not only would Black individuals feel safer and more welcome at a greater number of salon spaces; these businesses would also be able to reach an important demographic and increase their profits. Offer products for all hair types. If many salons cannot or refuse to service Black customers, it comes as no surprise that these same businesses often don’t sell products that work with natural hair. Stylists generally have useful advice to impart regarding which hair products to use and which to avoid, so it’s common to leave a salon visit with a bag full of products to take care of your new do. However, salons may not sell products that are appropriate for certain textures, especially Black hair. When stores like Target and Walmart already carry limited options—and sometimes none at all—for Black customers, it’s doubly frustrating to not be able to find appropriate hair products at the local salon. In addition to hiring stylists trained to work with Black hair, salons should carry products for all hair textures. Again, the burden shouldn’t be on Black customers to figure out where they can purchase items that fit their hair texture; an inclusive salon welcomes all hair types and treats them with dignity. In 2022, it shouldn’t require detective work to be able to find the right shampoo and conditioner, right? Support LGBTQ+ customers and their hairstyles. While we’ve focused on Black hair for the majority of this post, as Black individuals experience the highest rates of discrimination for their natural and protective hairstyles, we also want to highlight the queer community. Like the kaleidoscope of LGBTQ+ identities, queer people don a multitude of hairstyles, at times flouting gender norms. Some lesbians, for example, prefer to wear their hair short, while some gay men sport longer hairstyles. These are only two, very limited examples, but the point is that queer individuals may have hair that contradicts societal expectations. As such, a salon should support queer people however they want to style their hair. Are you a woman who wants a buzz cut? Great. Are you a man who wants an ombré? Fantastic. Are you a non-binary individual who wants an asymmetrical cut with highlights? Phenomenal. Inclusivity at salons may range from offering a wider variety of hair products to hiring staff members trained in styling Black hair. The recommendations we’ve included in this informal guide won’t necessarily happen overnight, but we hope they help salons—and other businesses that work with hair in some way—consider how to make their practices more inclusive. Every type of hair is beautiful and should be celebrated. It’s a shame that only in 2022 are we in the process of passing a bill to ban race-based hair discrimination, but it’s an important start. Salons can build off the momentum of legislation like the CROWN Act by taking concrete steps, as outlined above, to celebrate individuals regardless of their hair texture or style. Know of a salon doing great work related to inclusivity? Leave them a review on the Inclusive Guide at inclusiveguide.com.

0 Comments

In addition to the harmful impact of implicit ableist practices, beliefs, and ideologies, there are a myriad of physical barriers that continue to perpetrate structural ableism. Structural ableism takes on many forms. From the abhorrent Chicago Codes of 1881, which prohibited the public appearance of individuals with certain physical disabilities, to the lack of wheelchair accessibility in a restaurant bathroom, ableism has long permeated time and industry. The American Disability Act (ADA), modeled after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibits discrimination based on disability and provides a guideline that covers employment, access to government services, and spaces with public accomodation; such as restaurants. However, these institutions continue to neglect some of the most literal forms of implicit structural ableism– physical and informational inaccessibility. Here are a few examples of physical and informational ableism that produce tangible discrimation that harms the disabled community. Insufficient Physical Accessibility: Restaurants that don’t have adequate seating arrangements such as height, spacing, accessibility for wheelchairs, adaptive equipment such as braille menus or access to sign language are just a few ways that implicit ableism functions in dining spaces. As well as owners that put off installation of wheelchair accessible bathrooms or a ramp at a step entryway. Photo from “?@$&! I can’t get in!” blog. Each unnecessary barrier in an organization, a business, or public space actively limits disabled folks mobility. Further isolating and putting yet another community out of reach. Albeit subconscious or overt, these physical barriers send a message that disabled people are not wanted and not welcome. Informational inaccessibility In 2020, the Colorado Restaurant Association was informed that a Douglas resident with visual impairment had been filing lawsuits against Colorado businesses, including restaurants, due their websites being non-compliant with the American Disabilities Act. Though the ADA was written before the internet was a widely used resource, websites are considered to be spaces of public accommodation– therefore, covered under the ADA. Failing to provide communication and information through alternative formats, such as websites and digital media, continues to impoverish and isolate people with visual, hearing, and communication disabilities. Photo from Brewability Although the American Disabilities Act is one of the most comprehensive forms of civil rights laws to pass legislation in U.S. history, structural ableism continues to marginalize disabled communities across expression and industry. People with disabilities deserve access to have the same ease of access to an excellent dining experience as anyone. Making public spaces and businesses accessible should be considered a standard vs an accommodation.

Inclusive Guide hopes that we have your support in our journey to make accessibility a standard in the restaurant industry. Know of a restaurant doing great work in accessible dining? Submit a review at InclusiveGuide.com. Sources: Adams, Philip. “How to Find WheelChair Accessible Restaurants Near You.” ?@$&! I can’t get in!, 24 Jun. 2016, blog.icantgetin.com/wheelchair-accessible-restaurants-near-me/. Accessed 16 Mar. 2022. Pulrang, Andrew. “Ableism Is More Than A Breach of Etiquette.” Forbes, 17 Feb. 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2022/02/17/ableism-is-more-than-a-breach-of-etiquette---it-has-consequences/?sh=5d1d10b77b7f. Accessed 7 Mar. 2022. Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 328 (1990). https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm Accessed 7 Mar. 2022. Crop tops for men. Button-ups for women. Gender-neutral underwear. In the Year of Our Lord 2022, it’s obvious more than ever before that fashion is for everybody. For too long our country, as well as various societies around the globe, have clung to unquestioned constructs that limit the possibilities of fashion. But folks like Harry Styles, Janelle Monáe, and many others, especially those within the trans and non-binary communities, have shown us the fabulousness of wearing what you want, when you want—no matter society’s arbitrary standards or gender designations for clothing.

Though the Pandora’s box of fashion continues to crack open more every day, there’s still a long way to go. At Inclusive Guide, we’re well aware that the better, more welcoming fashion world we envision won’t emerge overnight. Individuals may choose to flout societal expectations and express themselves in beautiful ways, but the fact remains that most retailers and fashion designers have work to do to make their clothing options more inclusive and accessible to all. We offer the following short and informal guide so that businesses may start to think about incorporating inclusivity into their practices and decision-making. * Carry a range of sizes to accommodate all body types. Ever found a cute top at a store, but it’s not in your size or it just doesn’t fit right? It’s frustrating! Sure, you can go to a tailor, but that costs extra time and money most folks don’t have. And that doesn’t account for those who need to size up their clothes. Carrying an assortment of tall sizes and XL options (and that means the 4Xs, too!) would not only make customers happy but also benefit a company’s bottom line—indeed, the average woman in the United States wears a size 16, which is roughly equivalent to a 1X. However, this doesn’t mean maintaining the status quo of only offering plus sizes for clothes that are dark, loose-fitting, or overall drab in appearance; everybody deserves to feel sexy regardless of body type. And if you’ve been to any brick-and-mortar retailers recently, you might have noticed the plus-size section off to the side, not integrated with the rest of the clothing options. That ain’t cool. All clothing sizes, from petite to 5X and larger, should be both available and easily accessible within stores. Rethink gendered displays and marketing. In a perfect world, clothes wouldn’t be gendered, period. There’s nothing inherently feminine about a dress or masculine about a suit. Yet, like public restrooms, clothing displays at practically every retailer are separated into men’s and women’s sections. This setup alienates trans and non-binary customers, as well as those who may be gender-nonconforming and simply want to don a different style. Collapsing the gender divide across both brick-and-mortars and online retailers honors the diversity of gender expression while also reaching a market of LGBTQ+ individuals often disregarded as consumers with buying power. Because the gender binary is so ingrained within society, it may not be possible for a store to go completely gender-free in its clothing displays. If this is the case, a business should at least emphasize in marketing efforts that its products are available for all. A bigger step would be hiring gender-diverse models to showcase clothing options. And there are always gender-neutral items for businesses to carry, such as TomboyX underwear or Phluid Project makeup. Provide options for disabled individuals—or offer to tailor their purchases for free. Clothing for disabled people is often referred to as adaptive and usually entails alterations made after a garment is already produced. Inclusive fashion, however, should be the reverse—clothes designed from the outset with disabled individuals in mind. While these garments are, unfortunately, only beginning to gain traction within the fashion world, businesses can support disabled folks by offering what inclusive options are available, such as Care + Wear, which features designs with chest port access, or Friendly Shoes, which sells Parkinson’s-focused footwear. If not possible to carry these items, a business could provide their disabled customers with free tailoring services. Because every person’s body is different, some off-the-rack options, no matter how they were designed, might not fit certain individuals’ needs. In this case, tailoring might be the only option, but disabled people shouldn’t be required to bear the financial burden of altering their clothes, especially when the fashion industry has overlooked—and still overlooks—disability in clothing design. This isn’t a perfect solution, but in the absence of available (and affordable) options, the least a business can do is demonstrate to disabled customers that it cares about their needs and is willing to support them however it can. * Inclusive fashion requires a major shift in existing business models. Clothes should be available, accessible, and ultimately comfortable for all people, not a narrow set of individuals often represented by models of European descent with slim bodies. A few steps toward inclusivity on the business end include carrying a range of sizes, rethinking gendered clothing displays, and offering garments for disabled individuals (or providing disabled customers with free tailoring services in the absence of such items). These steps don’t capture the entirety of what must be done to make the fashion industry inclusive, of course, but they’re a start. We hope you support us in our journey to promote inclusive fashion across brick-and-mortar stores and online retailers. Know of a business making strides in inclusive fashion? Leave a review today on the Inclusive Guide at inclusiveguide.com. We at Inclusive Guide condemn Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s recent transphobic directive to investigate the families of children who have received gender-affirming care. As an organization with several gender-expansive employees, we intimately know what harm such directives and other political moves can cause to trans and non-binary individuals. If you live in Texas, we implore you to vote early to try to oust Abbott using the democratic process. We also urge Texas residents to write and call your senators and representatives, as well as support or join human rights–focused political organizations, such as the Texas Civil Rights Project and Texas offices of the Human Rights Campaign.

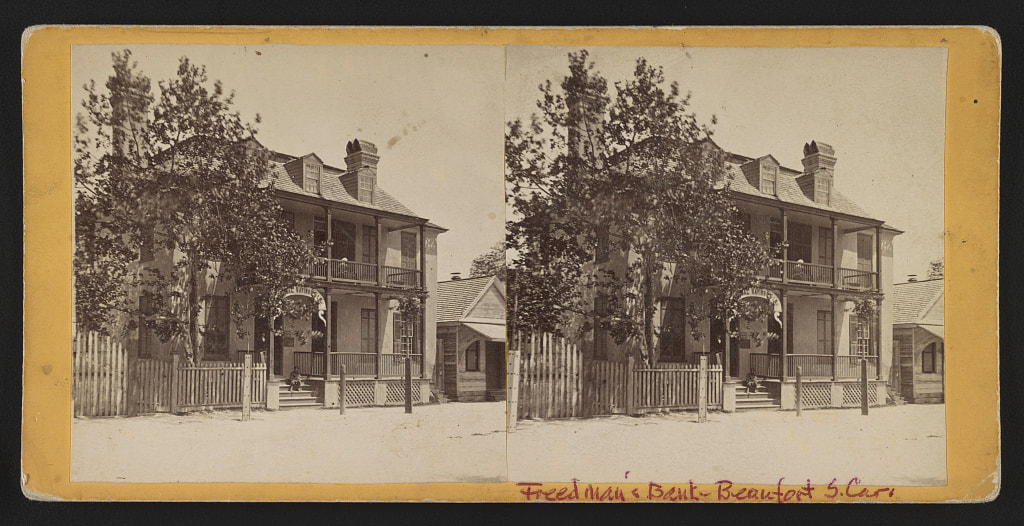

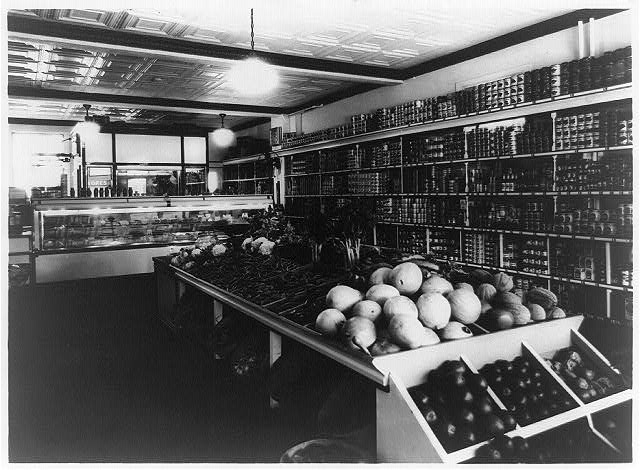

In 2020, The Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for queer individuals, found that 52% of all trans and non-binary people aged 13–24 in the United States seriously considered killing themselves. More specifically, a high rate of young people of color attempted to kill themselves, the highest being 31% for Indigenous youth. (The two second-highest groups were Black and multiracial young people at 21% each.) With statistics such as these, we need to do everything in our power to nurture our trans and non-binary youth, not prevent them from receiving life-saving care or resources. Abbott’s recent directive only inflames an already unacceptable situation for our country’s gender-expansive community. Additionally, research doesn’t support the misinformed idea that gender-affirming care is “child abuse.” In fact, the opposite is true: A December 2021 study in the peer-reviewed Journal of Adolescent Health asserts that gender-affirming hormone therapy is tied to lower rates of both suicidal ideation and depression in gender-expansive youth, as well as a considerable reduction in suicide attempts among trans and non-binary people younger than 18 years old. Major US medical organizations, including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Psychological Association, also support gender-affirming care models for young people. Fortunately, legal experts such as Chase Strangio of the American Civil Liberties Union say the Texas governor’s directive is not legally binding. Texas’ process for child abuse investigations remains the same, including the standard required to initiate an investigation in the first place. However, Abbott’s anti-trans posturing causes needless stress, anxiety, and fear among gender-expansive young people and their families in Texas. His use of transphobic rhetoric and symbolic political moves exploits the real lives of trans and non-binary youth as a bargaining chip for his ultra-conservative constituents. And while this directive may not be enforceable, it signals to Texans, and people throughout the country, that it’s acceptable to disregard the humanity of one our most vulnerable populations—a sentiment that does lead to consequences for the trans and non-binary community, such as transphobic bathroom bills and sports regulations. We hope you stand with us against Abbott’s cruel efforts to dehumanize our gender-expansive colleagues, friends, and family members. If you live in Texas, we implore you to vote early, join social justice campaigns, and/or contact your senators and representatives. (If you’re unsure who represents you, the Who Represents Me? tool can help you find your congressional district.) Let Abbott have a piece of us. Sources Carlisle, Madeleine. “‘It’s Creating a Witch Hunt.’ How Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s Anti-Trans Directive Hurts LGBTQ Youth.” TIME, 24 Feb. 2022, time.com/6150964/greg-abbott-trans-kids-child-abuse/. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022. Ennis, Dawn. “‘Terrible Time for Trans Youth’: New Survey Spotlights Suicide Attempts—and Hope.” Forbes, 29 May 2021, forbes.com/sites/dawnstaceyennis/2021/05/19/terrible-time-for-trans-youth-new-survey-spotlights-suicide-spike---and-hope/?sh=73724425716e. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022. Green, Amy E., et al. “Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy with Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health, in press (published online 14 Dec. 2021), pp. 1–7, doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022. This is the fifth and final post in our “Then & Now” series for 2022’s Black History Month in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Similar to the difficulties Black individuals have faced throughout US banking history, Black-owned businesses still encounter problems of funding and overall support to this day. A good, although rough, starting point to begin tracing this problematic history lies in the aftermath of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Known informally as “Black Wall Street” for its vibrant entrepreneurial community and breadth of Black-owned businesses, the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was violently attacked on May 31 by a relentless white mob. Numerous Black residents were killed (it’s estimated between 55 and over 300), while more than a thousand homes and businesses were looted, then set ablaze. The once-thriving neighborhood and business community, which was founded in large part by the descendants of slaves, was essentially razed overnight—all because a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner tripped and accidentally grabbed a white girl’s arm in an elevator. Besides the horrific nature of the massacre being covered up by Tulsa’s white community for several decades (it wasn’t until 2000 that the tragedy was even included in Oklahoma’s public school curriculum), the Black neighborhood received little to no support from organizations and institutions in the aftermath of the destruction. Insurance companies refused to pay Black property owners’ claims for damages, while a fire ordinance was enacted to deter the community from rebuilding. Many families left to start over elsewhere, but those who did stay had to rebuild Greenwood themselves—and with opposition from Tulsa’s white community. “Rear view of truck carrying African Americans during the Tulsa, Oklahoma, massacre of 1921” by Alvin C. Krupnick Co. (1921). Public domain. This blog post doesn’t do the Tulsa Race Massacre justice, as there are many more important details about the event that deserve one’s attention. (We encourage you to learn more about the massacre by consulting the sources linked below.) We also recognize that Black businesses across America faced difficulties much earlier than 1921. However, this tragedy exemplifies the lack of support Black business owners often receive when they need it the most, a trend that haunts our country today. In 2014, for example, Los Angeles business owners Moses and Maurice Harris had to navigate an unwelcoming financial industry to jump-start their coffee shop, Bloom & Plume. Despite Moses’ background in banking and his financial know-how, as well as Maurice’s entrepreneurial experience, the brothers were rejected for a business loan by some 35 to 40 traditional banks. The number of rejections becomes even more suspect considering that Moses possessed significant collateral through home equity and both brothers boasted a steady income. Eventually, a Black-owned community bank provided the two with a loan for their coffee shop. Though the existence of such financial institutions represents a triumph for the Black business community, Black-owned companies shouldn’t be relegated to community banks for financial support. As history shows us, the burden always falls upon Black individuals to lift themselves up, but it shouldn’t be that way. The value of Black-owned businesses extends far beyond the Black community itself, offering myriad benefits to society more broadly.  “GGM_2635” by Gabriel Garcia Marengo (2018). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. As a Black-owned company, Inclusive Journeys understands firsthand how difficult it is for Black business owners to navigate the financial landscape. We hope that the Inclusive Guide, in small part, uplifts the many Black-owned businesses doing the tough work of inclusion within our communities. At the company level, we hope that the work of Inclusive Journeys proves to venture capitalists and other, more traditional sources of funding that Black-owned businesses are an asset, not a risk. If our work speaks to you, sign up for the Inclusive Guide today at inclusiveguide.com and start leaving reviews of businesses in your community. And, as always, we’d be immensely grateful if you donated to our GoFundMe campaign at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources Baboolall, David, and Earl Fitzhugh. “Black-owned businesses face an unequal path to recovery.” McKinsey Insights, 11 June 2021, mckinsey.com/featured-insights/sustainable-inclusive-growth/future-of-america/black-owned-businesses-face-an-unequal-path-to-recovery/. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. Li, Yun. “Black Wall Street was shattered 100 years ago. How the Tulsa race massacre was covered up and unearthed.” CNBC, 31 May 2021, cnbc.com/2021/05/31/black-wall-street-was-shattered-100-years-ago-how-tulsa-race-massacre-was-covered-up.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. Parshina-Kottas, Yuliya, Anjali Singhvi, Audra D. S. Burch, Troy Griggs, Mika Gröndahl, Lingdong Huang, Tim Wallace, Jeremy White, and Josh Williams. “What the Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed.” The New York Times, 24 May 2021, nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/24/us/tulsa-race-massacre.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2022. This is the fourth post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Throughout US history, Black individuals have experienced numerous examples of racial discrimination and general difficulties at financial institutions. This history comes into focus during the 1860s around the time slavery was abolished and Black Americans were granted citizenship (due to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, respectively). Specifically, in 1865, the US government chartered the Freedman’s Savings Bank, meant to provide Black individuals with both a safe place to deposit their income and basic financial education, services denied to them previously. Freedman’s Savings Bank started off well. Tens of thousands of Black customers collectively deposited millions of dollars into the bank, thus encouraging the financial institution to open branches across the country. But due to the volatile post–Civil War economy and mismanagement by white bank executives, who handled the Black customers’ savings riskily and inappropriately, the financial institution collapsed in 1874, leaving depositors in a precarious situation. Though the bank promised to return a portion of the savings lost to its Black customers, most individuals received either pennies on the dollar or nothing at all. “Freedman’s Bank Beaufort So. Ca.” by Hubbard & Mix (1863–1866). Public domain. The collapse of the Freedman’s Savings Bank helped promote a distrust of the financial services industry among Black Americans—and for good reason. Over the next century Black individuals would be regularly denied mortgages or auto loans, and if a credit line were successfully opened, the fees were often higher. Unfortunately, Black credit seekers experience similar examples of discrimination from financial institutions to this day. Even using a bank can be dangerous for a Black customer. Several instances of blatant racism have occurred in recent years at some of the country’s most well-known banks. At the end of 2021, Hopkins order picker Joe Morrow went to a U.S. Bank branch in Columbia Heights, Minnesota, to deposit his paycheck after a 12-hour shift at work. Despite having an account with the bank and his ID on him, Morrow was suspected by a branch bank manager of attempting to cash a fake check. The bank manager finally verified the legitimacy of Morrow’s check, but only after the 23-year-old Black man was removed by police, threatened with arrest, and placed in handcuffs. “U.S. Bank Tower Building, Lincoln, Nebraska” by Tony Webster (2018). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. In another example from 2018, Clarice Middleton tried to cash a $200 check at a Wells Fargo branch in Atlanta, Georgia, but three of the bank’s employees accused her of fraud and called the police. In that moment, Middleton thought, “I don’t want to die.” Although the police officer left without taking action and Middleton was eventually able to cash her check, the emotional and psychological scars remain. To make matters worse, after the incident, a Wells Fargo spokesperson claimed that Middleton started to shout “abusive and profane language” (she didn’t), effectively gaslighting her. The history of Black banking in America is a reminder that many basic services, such as access to a savings account, remain difficult for customers of color who continue to be racially profiled and treated disrespectfully by employees. At Inclusive Journeys, we condemn this discriminatory behavior and aim to cultivate a safer banking environment for Black and brown individuals. We encourage users to leave reviews of their experiences at banks, whether positive or negative, on the Inclusive Guide so that marginalized customers may know which financial institutions are safe for them to visit—and those which may not be. We also want to uplift the Black-owned banks that strive to make the financial services industry more welcoming and accessible to customers of color. Help us foster a better banking culture for Black and brown individuals. You can join our fight for justice by leaving a review on inclusiveguide.com and donating to our GoFundMe campaign at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources Flitter, Emily. “‘Banking While Black’: How Cashing a Check Can Be a Minefield.” The New York Times, 18 June 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/18/business/banks-black-customers-racism.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. “The Freedman’s Savings Bank: Good Intentions Were Not Enough; A Noble Experiment Goes Awry.” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, occ.treas.gov/about/who-we-are/history/1863-1865/1863-1865-freedmans-savings-bank.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. Rasmussen, Eric. “‘Banking While Black’: Police video shows how cashing a paycheck led to handcuffs.” 5 Eyewitness News (KSTP-TV), 7 Dec. 2021, kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/banking-while-black-police-video-shows-how-cashing-a-paycheck-led-to-handcuffs/. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. Williams, Mariette. “After years of banks overcharging and undervaluing Black customers, ‘banking Black’ is gaining popularity as an effective way to fight systemic racism.” Business Insider, 22 Feb. 2021, businessinsider.com/personal-finance/banking-black-americans-switching-banks-2021-2. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022. This is the third post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives—to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Then & Now: Supermarket Redlining While both retail and dining racism offer a clear history of segregation, discrimination, and injustice, the story of American grocery stores isn’t as black and white. A look at the past 60 years of the country’s shifting supermarket landscape reveals a set of insidious maneuvers that has, ultimately, perpetuated a racial divide in the US. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s led to many positive policy changes and helped foster a racial consciousness across America, but self-service supermarkets and chain stores viewed the situation differently. Their white customers were fleeing cities in favor of the suburbs where racial unrest didn’t appear as pronounced. Grocers could stay in the city, but at what cost? Seeing an opportunity to earn more profits, grocery stores followed their white customers to the ostensibly “safer” suburbs where they could open larger stores with bigger parking lots, wider aisles, and more food, all on inexpensive suburban land.

Detroit serves as a prime example of this divide. In 2020, the city only had three large supermarkets: a Whole Foods and two Meijer stores. Earlier, during the mid-aughts, Detroit didn’t have a single major grocery chain. This reality becomes even more concerning when considering the city’s population breakdown: 78% of Detroit residents are Black. There’s a clear connection between the white flight from the city and the lack of big supermarkets, especially when just outside Detroit there are several Kroger stores in a ring around the border. As Detroit Food Policy Council Executive Director Winona Bynum says, “Big chains don’t see Detroit as a place where they can make money. The perception is that Detroit is a big pit of poverty and Black people will steal you blind and try to get things for a nickel.”

On top of the problematic white flight of supermarkets, many Black people continue to report discrimination and racial profiling at grocery stores, including, among other examples, being followed while shopping, directed to the sales section, or outright ignored. Not only must urban customers of color travel farther to access more affordable groceries; they also become targets of discrimination when entering grocery store chains in predominantly white suburban areas.

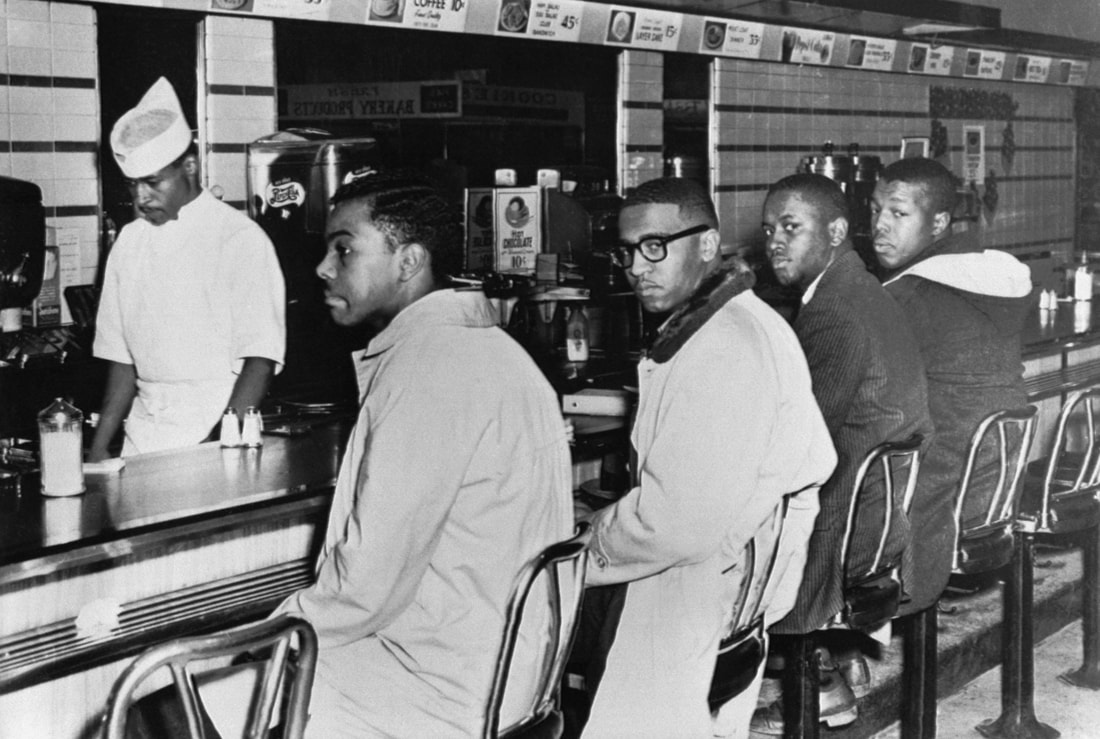

The history of supermarket redlining demonstrates why it’s more important than ever for us to support Black-owned grocery stores. One way to do this is by leaving a review of your favorite community supermarket on Inclusive Guide so that other customers of color will know it’s safe and welcoming. Conversely, you can use the Inclusive Guide to share any acts of discrimination or racial profiling you’ve experienced at a large grocery chain, thereby signaling to others that this store might not be a safe space for them. And, as the Inclusive Journeys team seeks to do with all businesses, we want to help by offering resources and training should a grocery store receive a low inclusivity rating. Help us cultivate a safer supermarket experience for shoppers of all identities. The first step is leaving a review on inclusiveguide.com. Sources Meyersohn, Nathaniel. “How the rise of supermarkets left out black America.” CNN Business, 16 June 2020, cnn.com/2020/06/16/business/grocery-stores-access-race-inequality/index.html. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. Perkins, Tom. “Why Are There So Few Black-Owned Grocery Stores?” Civil Eats, 8 Jan. 2018, civileats.com/2018/01/08/why-are-there-so-few-black-owned-grocery-stores/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. Robison, Daniel. “Racial profiling by retailers creates an unwelcome climate for black shoppers, study shows.” The Daily, 16 Nov. 2017, thedaily.case.edu/racial-profiling-retailers-creates-unwelcome-climate-black-shoppers-study-shows/. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. This is the second post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives–to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Then & Now: Dining Racism In addition to retail racism, Black patrons have specifically faced discrimination in dining situations, including at restaurants, coffee shops, and other establishments. Some of the earliest demonstrations during the Civil Rights Movement took place at lunch counters at popular chain stores. A famous example began on February 1, 1960, at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth, a former general-merchandise chain with stores across America. Four Black men studying at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NCA&T)—Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond—sat down at Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter and ordered coffee and donuts but were refused service. While they expected to be arrested, the four students were, for the most part, left alone and stayed until the store closed. The following day, Blair, McCain, McNeil, and Richmond were joined by other protesters; this second sit-in was covered by the local newspaper and television station. On February 3, the demonstration grew, with more than 60 students taking turns occupying every seat at Woolworth’s lunch counter. The momentum continued into February 4 and reached close to 300 protesters, including women and white students. This series of sit-ins at the Greensboro Woolworth jump-started a number of demonstrations to combat segregation, such as picket lines, boycotts, and other sit-ins. The Ku Klux Klan eventually became involved with the Woolworth sit-in and harassed protesters in hopes of deterring them. However, the demonstration only grew stronger, as the NCA&T football team joined the effort, as well as organizers for the Congress of Racial Equality, who helped train the students in tactics of nonviolent resistance. Several months later, Woolworth and other chains agreed to serve all customers at their lunch counters, marking one of the first major successes in desegregation (other than the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case a few years prior, which desegregated public schools). Much like retail racism, though, insidious forms of racial discrimination persist to this day at dining establishments. In 2019, for instance, Black Starbucks customer Lorne Green was targeted the moment he walked into the Brandon, Florida, coffee shop and went to the restroom. Starbucks staff incessantly knocked on the restroom door, asking if he needed the help of “fire rescue,” at which point he called the company’s corporate line and reported the incident. Uncomfortable, Green eventually left the Starbucks, but not without being issued a trespassing ticket from deputies called to the coffee shop. Although Green was able to team up with an attorney to try to have the citation dropped, this incident represents racial profiling at its worst. Moreover, Green’s case resembles an incident in 2018 during which two Black men, Rashon Nelson and Donte Robinson, were arrested after asking to use the restroom at a Philadelphia Starbucks.

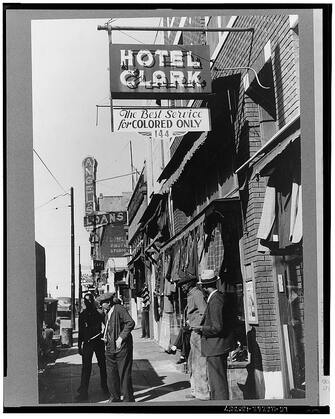

These examples highlight the continuing fight for racial justice, even at businesses like Starbucks that claim to have a “zero-tolerance policy” for discrimination. That’s why the Inclusive Guide is necessary—to help users navigate coffee shops and restaurants, among other businesses, safely and comfortably. On the business side, Inclusive Journeys plans to offer diversity, equity, and inclusion training and resources to companies, whether they be coffee giant Starbucks or a local business, so that their employees can help cultivate an inclusive environment for patrons of all identities. Join us as we strive to stop racism at coffee shops, restaurants, and other dining establishments. Sign up to review businesses at inclusiveguide.com, and consider donating to our project at gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Sources “2 Philadelphia men in Starbucks controversy speak out.” FOX 13 Tampa Bay, 19 April 2018, fox13news.com/news/2-philadelphia-men-in-starbucks-controversy-speak-out. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. “Civil Rights Movement History 1960.” Civil Rights Movement Archive, crmvet.org/tim/timhis60.htm#1960greensboro. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. “Man says he was kicked out of Brandon Starbucks because he’s black.” FOX 13 Tampa Bay, 9 May 2019, fox13news.com/news/man-says-he-was-kicked-out-of-brandon-starbucks-because-hes-black. Accessed 1 Feb. 2022. This is the first post in our “Then & Now” series in which we highlight an example of business-related discrimination in Black history and pair it with a similar event(s) during our modern day. We share these comparisons to demonstrate the continuing fight for Black justice after the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Despite popular conceptions of America existing as a “post-racial” society, racism lives—and thrives–to this day, representing the need to further our pursuit of equity for all. Then & Now: Retail Racism

By contrast, in Washington, DC, Woodward & Lothrop was known for its separate entrances, elevators, restrooms, and drinking fountains. On the workforce side, Black applicants for certain department stores, such as Marshall Field & Co. in Chicago, were overlooked because of their skin color. Indeed, a company representative told Chicago’s Commission on Human Relations that Black workers would “negatively affect the character, atmosphere, and flavor” of the store.

Missouri’s Brentwood neighborhood. The three teens were followed around the store by employees, prompting the boys to leave. One of the friends forgot his hat inside the store, but when the three of them returned to Nordstrom Rack to find it, an older white woman called them “a bunch of bums” and asked whether their families would “be proud of what [they’re] doing.” Lee, Rogers, and Taylor left a second time, but they decided to return and shop there anyway to “demonstrate to them that we aren’t thugs.” In the checkout line, however, the boys overheard employees talking about calling the police. As expected, when the police arrived, the officer discovered that nothing had happened at the store. Thankfully, the teenagers weren’t injured or taken into custody during the ordeal, but what they did experience was an emotionally and psychologically exhausting example of boldfaced discrimination from Nordstrom Rack’s employees. The 2018 Brentwood incident is only one of many contemporary examples of retail racism. From a woman being stopped and searched at a Macy’s in San Jose, California, to former President Barack Obama being followed while shopping at department stores, Black shoppers are still made to feel unsafe and uncomfortable in retail settings. All this is why at Inclusive Journeys, we aim to shift workplace culture so that all shoppers feel welcome. With the Inclusive Guide, users can share their experiences at different businesses and rate them based on inclusivity-focused criteria. Other users can then see these reviews and determine whether they want to support a business based on its inclusivity rating. However, if a business receives a low rating, we want to help by offering diversity, equity, and inclusion training and resources so that the company can work on cultivating a more inclusive, equitable atmosphere. We strive to make workplaces better holistically—on both the customer side and the business end. Support our journey to end retail racism and systemic oppression more broadly. You can sign up to start reviewing businesses at inclusiveguide.com. SourcesFavro, Marianne. “San Jose Woman Accuses Macy’s of Racial Profiling in Stop-and-Search Incident.” NBC Bay Area, 15 May 2018, nbcbayarea.com/news/local/san-jose-woman-accuses-macys-of-racial-profiling-in-stop-and-search-incident/178016/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

Lisicky, Michael. “Racial Injustice Outlived The American Department Store.” Forbes, 6 June 2020, forbes.com/sites/michaellisicky/2020/06/06/racial-injustice-outlived-the-american-department-store/?sh=14d07bbf7623. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. Seipel, Brooke. “Nordstrom Rack apologizes after calling police on 3 black teens who were shopping for prom.” The Hill, 9 May 2018, thehill.com/homenews/news/386859-nordstrom-rack-apologizes-after-calling-police-on-3-black-teens-who-were?rl=1. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. Singletary, Michelle. “Shopping while black. African Americans continue to face retail racism.” The Washington Post, 17 May 2018, washingtonpost.com/news/get-there/wp/2018/05/17/shopping-while-black-african-americans-continue-to-face-retail-racism/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. When I heard the verdict was about to come in, I turned on the tv and called Parker. We go through these things together, not just as business partners but also as friends. As Black women. We are both married to incredibly supportive white allies, who are abolitionists as well as our husbands. But there’s something about being in solidarity with another Black person at times like these that even the best partner couldn’t quite understand.

|