|

Originally established in 1973, Roe v. Wade was a landmark decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution would generally protect a person’s liberty to abortion care. To provide a bit of background on the case, in 1970 Jane Roe (a fictional name used in court documents to protect the plaintiff’s identity) filed a lawsuit against Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County, Texas county, challenging a law making abortion illegal except by a doctor’s orders to save a woman’s life. Roe, a resident of Dallas County at the time, alleged that the state laws were “unconstitutionally vague and abridged her right of personal privacy, protected by the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments.” In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Jane Roe, holding that “a woman’s right to an abortion” was implied in the Fourteenth Amendment, thereby striking down a Texas statute banning abortion and effectively legalizing the procedure across the country. The discussion and subsequent legislation around abortion centered the preservation of human life, preceded only by the concept of when a human life begins. Ironically, there is often little to no consideration for the hundreds of millions of people alive today—including the lives of folx who bear children and children themselves. Social constructs such as white supremacy, classism, patriarchy, and queer- and transphobia are active measures built to deny access to resources that these very same individuals and their children need to thrive, let alone survive. Within the past thirty to sixty days alone, this country has witnessed multiple mass murders, skyrocketing housing, fuel, and food costs, an increase in food deserts, and an enormous shortage of baby formula. In the US, preservation of human life has always been tied to situations and circumstances that are informed by the personal beliefs that have since proliferated throughout the socioeconomic systems that exist today. So, is the overturning of Roe v. Wade really a motion of virtue in the consideration of human life, or is it a desparate attempt to maintain cis-hetero white supremacist dominance and ensure future laborers through another person’s womb? In contrast, millions of people have taken to the streets to protest the recent ruling. Though we stand in solidarity with the pro-choice movement and fervently support body sovereignty, we must critique the queer and trans erasure at the foundation of pro-choice organizing. Much of the discourse and public outrage around overturning Roe v. Wade centers cisgender women’s right to choose, completely overlooking trans folx and their deservedness of the same autonomy, as well as access to abortion and reproductive care. For the queer and trans community, access to proper healthcare has been manufactured to be as difficult to attain as possible. From routine check-ups and specialized care to gender-affirming surgery, accessing healthcare in any capacity is a perpetually arduous task. As anti-LGBTQIA2S+ laws run rampant across the country, queer and trans erasure in rhetoric around body autonomomy, abortion, and reproductive care is a reminder that queer and trans folx are not considered and not wanted. PEOPLE deserve the right to choose. PEOPLE deserve access to proper reproductive care. If we are to say that abortion and reproductive rights are human rights, then we should be considering every human’s right to choose. After nearly 50 years, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned one of the most important and progressive federal protections in the country’s history, thereby violently unraveling the foundation of a multitude of rights promised to us by our VERY OWN CONSTITUTION. To be frank, we’re not entirely sure how legitimate “rights” can be in a nation built on stolen land by people who were kidnapped and enslaved. July 4th, the United States’ Independence Day, is less than a week away. How is it that a nation can celebrate its own independence when a portion of its people are forced into bondage? If this truly is “the land of the free,” then our leaders have a duty to question what freedom really is and to whom it is extended. Abortion and reproductive care are healthcare. Abortion and reproductive rights are human rights—a freedom that should be extended to everyone. Inclusive Guide stands for reproductive justice for all. Statements from within the Company “As a person adopted in the United States after 1973, I want to make sure I’m being abundantly clear when I say that adoption is not an alternative to abortion. Adoption when chosen is a brave decision that a birthing person makes to allow their child to be parented by a different family. Adoption is also often made by choice on the [part of the birthing parent]. This issue is also key to our consideration of bodily and familial autonomy and how we plan to support that. Abortion is healthcare and should be available safely and affordably to every person who finds themselves need to consider one. Regardless of the other [options] that may come available.” Sources Edwards-Levy, Ariel. “Broad Majority of Americans Didn't Want Roe v. Wade Overturned, Polling Prior to Supreme Court Decision Shows | CNN Politics.” CNN, Cable News Network, 24 June 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/24/politics/americans-roe-v-wade-polling/index.html. Rajkumar, Shruti. “With Roe v. Wade Overturned, Disabled People Reflect on How It Will Impact Them.” NPR, NPR, 25 June 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/06/25/1107151162/abortion-roe-v-wade-overturned-disabled-people-reflect-how-it-will-impact-them. “United States of America 1789 (Rev. 1992) Constitution.” Constitute, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/United_States_of_America_1992.

0 Comments

Like most things in our world, the travel industry has historically left many people behind. From outdoor recreation companies only showing white, able-bodied individuals in their ads to travel companies and bloggers ignoring the accessibility concerns of certain trips, there’s a lot to address. So where does one start? This blog post will offer a couple of inclusivity-focused tips for those involved in the travel industry. If we truly want all kinds of people to explore outdoor spaces or book exciting trips around the country/world, we need to ensure that these destinations actually welcome individuals of various backgrounds. Diversity itself is important, but we need to take the next step and make travel inclusive. 1. Disclose Important Accessibility Information One of the largest groups excluded from travel experiences is the disabled community. Ideally, every space should be created with a range of body types and ability levels in mind, but the unfortunate reality is that many spaces aren’t disability-friendly at all. However, one thing travel companies and content creators can do now is explicitly describe a space’s physical environment for potential travelers. Some basic questions to consider: Is the ground level? Are there inclines or steps? How big is the overall space? How wide are the pathways throughout the space? Are the pathways composed of dirt, gravel, or something else? Are there any specific accessibility features that have been included, such as boardwalks or ramps? Of course, these are only a few of many possibilities, as each space will be different, but answers to questions like these will help form a clear picture of the space being explored. Such information is important to disclose because it will signal to individuals whether or not they can access, or feel comfortable within, a certain outdoor space or travel experience. If, for example, a wheelchair user goes on a hike thinking the trail is accessible but discovers along the way that there are several steps to ascend, that’s a problem—one that could have easily been addressed had folks known ahead of time just what they might encounter on said hike. Accompanying this information should be several pictures that provide a comprehensive look at what somebody might see on the trip. This isn’t for aesthetic reasons but, rather, providing a way for potential travelers to visualize themselves in the space being pictured. If you’re a travel blogger taking cute pictures of the trip anyway, then it shouldn’t take much extra effort to document the physical environment you’re engaging with. A word of caution: When sharing this information, don’t assume a space is accessible simply because the ground is level or there’s a ramp for wheelchair users. The disabled community isn’t a monolith. As such, describing the space itself rather than making a judgment about it will go a lot further in helping potential travelers access it. Overall, information is power. If universal design still has a long way to go in terms of being implemented throughout our country (and the world), then the least someone should be able to do is decide for themselves, with all the information available, if a trip is worthwhile. We need to rethink spaces and make them accessible to all, yes, but in the meantime, we can pay our information forward. 2. Consider the Safety of Marginalized Travelers It’s easy to simply say that a space welcomes everybody regardless of identity, but the reality is that too many spaces feature very few people from marginalized backgrounds. This is especially true for outdoor spaces. For this tip, it might be helpful to more specifically think about inclusion over diversity. For example, many BIPOC individuals engage in outdoor recreation, but if you work for a travel company that’s advertising a certain outdoors activity in an area that’s mostly trafficked by white people, it wouldn’t be wise to suggest just how “comfortable” or “welcome” a person of color would feel in said area. This advertising tactic screams of “diversity on the books” without actually making sure that marginalized individuals are included in the activity or within the space in general. Ultimately, inclusion in this sense boils down to safety. Not being welcome or comfortable in a space might translate into being insulted, followed, or even physically assaulted. Accordingly, in addition to accessibility information, travel companies and content creators should disclose any safety concerns about certain trips or spaces. Some basic questions to consider: Do BIPOC, queer, disabled, and/or other marginalized individuals often travel to this space? Have travelers from one (or more) of these historically disenfranchised groups written about this place? How conservative are the surrounding areas? Questions like these will help individuals of different groups determine how comfortable they'd be should they embark on a certain travel experience. Like accessibility, safety for marginalized groups isn’t something that’s going to be worked into every space overnight. Changing the culture of our country, specifically within the travel industry, will take time. For now, though, a queer person or BIPOC individual shouldn’t have to go digging to determine if they’d feel safe on a specific hike—that information should be readily available.

Most of you have probably heard of DWB: “driving while Black.” This term refers to the difficulties faced specifically by Black drivers, including being yelled at by highway patrol officers, being forced into random vehicle searches, or worse—being physically assaulted due to racial profiling. Unfortunately, DWB extends to other types of personal transportation in America, such as RVs. RVing may be considered a quintessential American pastime—images of the “great American road trip” come to mind—but this activity has risks for BIPOC, especially Black families. As you know, our co-founder Parker is on a road trip across the American South and Midwest with her mixed-race family to raise visibility for BIPOC travel and outdoor recreation. However, things aren’t magically discrimination-free in 2022 for Parker’s family or other BIPOC families. When on a road trip today, there’s a high likelihood families will pass through predominantly white communities full of conservative residents with their Trump signs still up; in fact, this was one of the first things Parker encountered on her journey. Even if nothing happens when passing through these towns, the mere anxiety of mentally preparing for a list of what-ifs puts strain on those traveling, especially the parents of children of color. Moreover, as we discussed in earlier blog posts, sundown towns were in full force in certain areas until the 1970s, and national parks that were located in segregated parts of the country during Jim Crow upheld the local “separate but equal” policies, thereby making outdoor recreation less safe for Black families. American road trips, whether as the mythology we see satirized in National Lampoon or the practical, lived experience of them, are overwhelmingly white. Some Black men from the South remember hearing the story of “the Bogeyman in the woods” growing up, which was often code for “the KKK will get you.” While a lot has changed for the better since the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, these childhood stories stick with people. You don’t simply forget the racism you’ve experienced—and that you’ve been taught to be wary of—because businesses are legally obligated to say they don’t discriminate based on race. Racism lives on, however insidiously. Fortunately, there are groups trying to make activities like RVing more welcoming and comfortable for Black individuals. The National African American RVers’ Association, for instance, is one organization that’s on a mission to connect Black RVers and their families around the US. While many Black people have been discouraged from outdoor recreation because of a lack of representation and inclusion within the travel industry, a history of racism in the outdoors, and other legitimate concerns, there does exist a community of Black outdoor enthusiasts. You may not see a Black family hitting the road on the latest RV ad, but there are many Black and mixed-race families, such as Parker’s, enjoying this American dream—you just have to pay attention. So what can you do to help make Black individuals feel more comfortable RVing or engaging in outdoor recreation? If you work for a national park or interpretation service, you could reflect on and update your educational content to ensure that it doesn’t tell history from a “white victor” perspective, thus allowing BIPOC to be a more significant part of the narrative. If you’re an outdoor recreation retailer, you could represent BIPOC in your advertising and even team up with folks like KWEEN WERK to encourage more people of color to enjoy the outdoors. Or if you’re a fellow RVer, you could simply check yourself and your privilege when interacting with travelers of color on the road or at campgrounds. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about outdoor recreation for BIPOC. Sources Dixon, Nanci. “Where are all the Black RVers? Why the outdoors isn’t as inclusive as you think.” RVtravel, 15 Oct. 2020, rvtravel.com/blackrvers970. Accessed 29 June 2022. “National African American RVers’ Association.” NAARVA, naarva.com. Accessed 29 June 2022. In his famous documentary, Ken Burns called national parks “America’s best idea.” When individuals think of the United States, they often conjure images of wilderness in the American West documented by Burns, such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. These spaces, which have been preserved through the National Park System, are associated with environmentalists like Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, the latter of whom founded the Oakland-based environmental justice organization Sierra Club. To think of Yellowstone, for example, is to think of America itself. But behind this grand narrative of conservation is a complicated racial history, one dotted with segregation, prejudice, and white privilege. During the Jim Crow era, national parks adhered to the “separate but equal” laws throughout the country, meaning outdoor spaces in the South and within border states such as Kentucky and Missouri were treated like segregated businesses. The park rangers who oversaw these spaces upheld segregation in campgrounds, restrooms, parking lots, cabins, and other public facilities. While some National Park Service employees desired to treat visitors equally, these officials were usually challenged throughout Jim Crow states by park superintendents, Southern congressmen, and various organizations. Even when governmental officials were sympathetic to the concerns of Black citizens, the actions and policies carried out often didn’t reflect a pro-Black sentiment for fear of upsetting white people with power. For instance, Harold Ickes, a known supporter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who held the position of Secretary of the Interior between 1933–1946, opposed marking facilities as “segregated” on maps, even if there was segregation in practice, so as to not perpetuate the idea of separation throughout the national parks. This idea may have seemed good in theory, but Ickes’ decision effectively made it more difficult for potential Black visitors to discern which spaces were safe for them. In the absence of word-of-mouth insights from fellow Black travelers, Black families would have to risk using a public resource, such as a picnic table or a bathroom, to ultimately determine if they were allowed to use it. Another questionable policy was upheld by the third director of the National Park Service, Arno Cammerer. He only wanted to build public facilities for Black visitors if there was sufficient demand for them. However, this policy didn’t apply to white individuals, and because of the perceived low interest in outdoor recreation from Black folks, facilities often weren’t built for Black use. And of the facilities that were created specifically for Black visitors, they were generally deprioritized, underfunded, and/or simply subpar compared to those built for white people. These historical accounts of Ickes and Cammerer represent only a fraction of the racist practices and attitudes that prevailed throughout the National Park System during the Jim Crow era. A couple of other distressing truths: Virginia’s Colonial National Historical Park was completely developed using segregated Black labor, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which was responsible for the development of various trails and park facilities, would segregate their workers across Southern parks. Even big names like Muir and Teddy Roosevelt are fraught with racism, as the former made derogatory remarks about Black and Indigenous folks and the latter viewed Filipinos, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans as inferior to Americans. Ostensibly bastions of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy, as Burns’ documentary might present them, national parks have been anything but. Two years ago, the Sierra Club’s executive director even called out the organization’s founder, the “father of national parks,” for his racism. On top of all this, Indigenous peoples have been forced off their homelands in the name of national park preservation. One of the earliest national parks, Yosemite bears a history of bloodshed as the Miwok people were exterminated and, if any settlements remained afterward, were evicted from their land. And even if Indigenous peoples weren’t murdered or relocated, they were denied access to national park resources, which they’d used for many years before the areas were deemed “national parks.” Unfortunately, the problematic history of the National Park System follows us to today. Inclusive Guide Co-founder Parker McMullen Bushman was recently denied entry at a California park by a worker there who thought she was going to do something “nefarious.” Although this particular area was open to the public 24 hours a day, Parker was racially profiled by the park official and subsequently treated unfairly. In Colorado, too, Black women have been harassed by park employees. Indeed, a group of Black women was recently stopped by a ranger at Rocky Mountain National Park because they were thought to be smoking weed, but they didn’t have any cannabis on them. These are only a couple of the many stories that exist for people of color at national parks across the US. Like any business, national parks aren’t neutral spaces. They contain human beings with the potential to discriminate, treat people unfairly, and maintain the status quo. National parks are only as welcoming as the people who oversee them. As such, park rangers and other staff should be aware of the biases they may bring to their management of parks and other wilderness areas. Segregation is no longer the law of the land, but like Parker’s experiences reveal, outdoor spaces aren’t free from microaggressions, prejudice, and unwelcoming attitudes in general. If we want everybody to use and benefit from national parks, we must manage them intentionally with an eye toward equity, inclusion, and social justice. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about the history of outdoor spaces. Sources

Colchester, Marcus. “Conservation Policy and Indigenous Peoples.” Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, March 2004, culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/conservation-policy-and-indigenous-peoples#:~:text=National%20parks%2C%20pioneered%20in%20the,central%20to%20conservation%20policy%20worldwide. Accessed 15 June 2022. Conde, Arturo. “Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘racist’ and ‘progressive’ legacy, historian says, is part of monument debate.” NBC News, 20 July 2020, nbcnews.com/news/latino/teddy-roosevelt-s-racist-progressive-legacy-historian-says-part-monument-n1234163. Accessed 15 June 2022. Melley, Brian. “Sierra Club calls out founder John Muir for racist views.” PBS Newshour, 22 July 2020, pbs.org/newshour/nation/sierra-club-calls-out-founder-john-muir-for-racist-views. Accessed 15 June 2022. “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” PBS, pbs.org/kenburns/the-national-parks/. Accessed 15 June 2022. Repanshek, Kurt. “How the National Park Service Grappled with Segregation During the 20th Century.” National Parks Traveler, 18 Aug. 2019, nationalparkstraveler.org/2019/08/how-national-park-service-grappled-segregation-during-20th-century. Accessed 15 June 2022. “sundown on chicago ave” by CGAphoto (2007). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. As you probably know, our co-founder Parker is on a road trip through the American South and Midwest. Her journey is a testament to how far we’ve come as a country—a Black woman with her white husband and mixed-race kids in an RV is, fortunately, no longer an automatic invitation for violence. However, people of color still face many challenges when it comes to travel, and not all spaces are safe, despite all the nondiscrimination laws on the books. That’s why we created Inclusive Guide and why we must continue the fight for equity and justice for all. Not too long ago—as recent as the 1970s, in fact—there existed blatantly racist areas throughout the country known as sundown towns. These all-white communities would display obvious signage telling Black travelers to stay out after sunset—or else. If Black travelers were spotted in a sundown town after dark, the community’s residents would often take extralegal measures, including verbal, psychological, and/or physical violence, to oust them. Black individuals were not only terrorized but also murdered in sundown towns. Various sundown towns existed across the South, but what some don’t know is that these racist communities could be found all around the United States. Oftentimes, there were more sundown towns in historically “free” states compared to their Southern neighbors. While some of these areas in the Midwest or West might not have labeled themselves as “sundown towns,” the fact remains that plenty of places across the country were hostile to Black individuals, even after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (And to no surprise, several of these former sundown towns remain predominantly white, sometimes upwards of 80 or 90 percent.) Moreover, sundown towns would intentionally exclude other people of color and historically marginalized groups. Prohibitions existed for not only Black individuals but also people of Chinese, Japanese, Native American, or Jewish descent, among others. Because of these discriminatory practices, traveling long distances by car was difficult for BIPOC individuals, making resources like The Negro Motorist Green Book necessary for travelers. The scary part of this history is that, well, sundown towns aren’t entirely a feature of our country’s past. These areas and attitudes persist into the 21st century but with more subtle tactics at individuals’ disposal to keep Black people out. BIPOC folks have time and again experienced discrimination in predominantly white communities—this is simply a fact. While such racism may manifest itself as a microaggression, such as an insensitive joke about Black people and culture or an uneducated comment about colorblindness, or as something more dangerous like yelling, stalking, or fighting, what ultimately ties these experiences together is a commitment to white supremacy. To unlearn white supremacy, we must know our racist past (and present). Confronting the reality of sundown towns and other deeply racist aspects of US history is only the first step, however. Educating oneself is significant, but we must also actively combat the white-supremacist systems that have been embedded within the fabric of our country. We believe that Inclusive Guide is one part of the solution, yes, but even more important is tackling policy at the highest level to ensure everybody feels safe, welcome, and celebrated no matter where they are. Whether it’s at the local coffee shop or a national park, people of all identities deserve to be comfortable being themselves. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about BIPOC travel. Sources

Coen, Ross. “Sundown Towns.” BlackPast, 23 Aug. 2020, blackpast.org/african-american-history/sundown-towns/. Accessed 1 June 2022. “Historical Database of Sundown Towns.” History and Social Justice, justice.tougaloo.edu/sundown-towns/using-the-sundown-towns-database/state-map/. Accessed 1 June 2022. Among one of the darkest periods of U.S. history lies the dawn of a new morning. A dawn that the National Museum of African American History & Culture considers as “our country’s second Independence Day.” Juneteenth (short for “June Nineteenth”) was initially organized in 1866 by freedmen. It was initially known as “Jubilee Day”. This monumental event has long been a celebration in the African-American community for over 150 years and is considered one of the longest African American celebrations in U.S. History.  The Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in 1863. However, it did not free all of those who were enslaved. Contrary to what many of us have been taught, the proclamation only applied to states that were under Confederate control, not slave-holding border states or rebel areas controlled by the Union. Thus states such as Texas, the westernmost Confederate state, continued enslavement for nearly 2 and 1/2 years beyond the initial emancipation. According to History News (i.e. History Channel), enslavers outside of the Lone Star state moved to Texas, viewing it as a “safe haven” for slavery. In some cases, enslavers withheld the information until after harvest season. Although Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered two months prior, It wasn’t until over 2000 union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas where General Granger read General Orders No. 3, which stated: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” Despite the fact that freedom didn’t happen overnight for everyone, celebrations broke out among those were newly freed. Subsequently, slavery was formally abolished by the 13th Amendment in December of 1865. In 1979, Texas became the first state to make Juneteenth an official state holiday. As of June 17th, 2021, Juneteenth became a national holiday.  Regardless of Corporate America’s misrepresentations of Juneteenth, this generational celebration is testament to Black Americans’ survival against systemic degradation. A testament to our continued perseverance in a country built on Indigenous land by the bone and blood of Black people and an ode to Pan-African liberation. The social structure that supported the historical atrocities in the development of this nation are the blueprint that continue to inform systems of oppression today. This is why we created Inclusive Guide. We believe that with critical analysis of our past, together we can set clear intention for a better future. Free of systemic oppression and rooted in equity for all of us. The historical legacy of Juneteenth. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2022, June 7). Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-legacy-juneteenth#:~:text=Freedom%20finally%20came%20on%20June,newly%20freed%20people%20in%20Texas

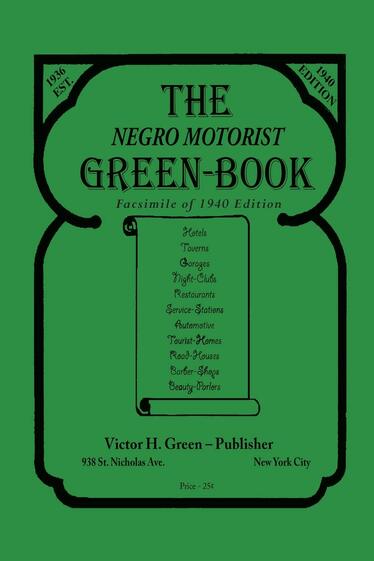

Nix, E. (2015, June 19). What is Juneteenth? History.com. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/what-is-juneteenth Parker here. I’m excited to share that this summer, my family and I are taking a two-week road trip through the American South and Midwest. We’re leaving Denver June 23 and will be driving down to Georgia and up through Michigan, all the way back to Colorado on July 10. I look forward to showing my three kids some of my favorite places and outdoor recreation areas along our path, such as Savannah and Tybee Island on the Georgia coast. While RVing across the country with your mixed-race family doesn’t seem like the most radical thing to do in 2022, safe and easy travel hasn’t always been the case for Black and brown folks. As I prepare for my family’s trip, I can’t help but think about the charged history of Black travel, including the spread of sundown towns, the Green Book, and all the other hoops people had to jump through in order to experience the “American dream” of vacations—because what isn’t more American than road-tripping.  I’ve lovingly titled my family’s journey “The Liberation Tour” because it hasn’t been that long in American history since a family like mine could safely realize this dream. Travel and outdoor recreation are historically white pastimes; not too long ago, whenever people of color wanted to participate in these activities, they needed to take extra precautions. Sundown towns—or white communities that have intentionally kept out Black people, often taking extralegal measures to terrorize and even kill those who remained past sunset—have only fell out of favor since the 1970s. To this day, there could still be unofficial sundown towns around the country, especially in communities that are mostly white. Colorado is home to more than 10 official sundown towns and over a dozen more that are “unlisted,” many of which are about an hour outside the Denver metro area, such as Burlington, Longmont, and Loveland. Within the last year, certain residents in one of the cities listed opposed measures that could have elevated the voices of its marginalized members in legislative decision-making. Many of the racist ideologies that cemented sundown towns of the midcentury still hold true today. Racism has no lane and knows no boundaries. Besides sundown towns, during Jim Crow, there were also rules of the road Black travelers needed to follow, such as pulling aside to let a white driver pass you. If you didn’t, that driver might get out of their car and physically assault you without consequence. Because every place had a different set of rules, Black travelers needed to know ahead of time where they could, say, pull over to relieve themselves or where their vehicle might be in danger of vandalism. During that time, many racist communities proudly advertised themselves as sundown towns on billboards, thereby alerting Black travelers of the perils that lay ahead, but guidelines for how to safely drive through certain areas of the country often went unstated and required insight from prior travelers to properly navigate. Unfortunately, these de facto driving guidelines still haunt us—every Black driver knows, even in 2022, just how dangerous it can be to be pulled over by a police officer. Enter The Negro Motorist Green Book. I’ve said this before, but I see my colleagues’ and my work at Inclusive Guide as taking the Green Book into the 21st century. Safety issues for travelers from marginalized communities persist to this very day. Before I discuss the need for resources like the Green Book today, I want to highlight a bit of the book’s history and why it was important. This guide was an essential tool for Black travelers in America. In fact, the inside cover of the Green Book stated, “Never Leave Home Without It.” It listed safe and welcoming spaces for Black travelers to visit between the years 1936–1966, with the ’66–’67 edition being the last issue printed, just after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. The credit for the original Green Book goes to Victor and Alma Green, alongside a Black, all-female editorial staff. Victor was a postal worker in Harlem. He asked everyone he knew to spread the word and send him postcards or letters about the safe places Black people could stay around the country. Like I mentioned earlier, many of the rules of segregated travel weren’t obviously posted. Because navigating Black travel was incredibly dangerous and unpredictable, the Green Book filled the safety gap and provided a comprehensive (yet ever-growing) list of all the safe places for Black motorists across the United States. One important Green Book site in the Denver area was Lincoln Hills. Founded in 1922 by E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt about an hour outside downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was one of the only Black resorts in the US during the 1920s. Individuals could buy 25 x 100 ft. lots at the resort, which they could then use to build summer cottages. Approximately 470 lots were sold by 1928. While the Great Depression financially prevented many Black families from realizing their summer-vacation dreams in the Colorado outdoors, lot owners still used their land as campsites or for day trips in the decades to come. You also didn’t need to own property at Lincoln Hills to take advantage of its offerings, including educational camps for Black girls and outdoor recreation activities. Plus, Black travelers were always welcome to stay at Winks Lodge, where they could eat home-cooked meals, enjoy a good cocktail, and listen to performances by talented Black musicians or writers. The passage of the Civil Rights Act may have made places like Lincoln Hills obsolete, but discrimination didn’t automatically end for travelers with one piece of legislation. Driving while Black remains a concern practically everywhere in the US. Some predominantly white communities act hostile toward travelers of color. And even if you might not be physically harmed in certain places, you’re still at risk of experiencing microaggressions and emotional or psychological abuse. The parallels between then and now are clear for people of color—the world still isn’t safe for us, nor is it safe for LGBTQ+, disabled, and other marginalized folks. Take my own family, for instance. While traveling, we’ve been stared at, questioned, and followed just for existing in certain places, especially throughout the South. Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case that banned laws prohibiting interracial marriage, may have been passed in 1967, but from my own experiences living in the world as part of a mixed-race family, I can tell you that some people still don’t like to see a white man and a Black woman together. Although I can take the heat, I don’t want my kids to experience this discrimination—and they shouldn’t have to in the first place. All this is why we need resources like Inclusive Guide to help travelers navigate the messy world of oppression. There’s a disconnect between our country’s official nondiscrimination laws and the unofficial discriminatory behavior that actually occurs. People still need to know which spaces are welcoming and which ones might be uncomfortable for them to be in, and this information can only be known through lived experience. Like the network of Black travelers that made the Green Book possible, those of us at the margins of society must share our insights and support one another. It’s time for us to reclaim travel.  Beyond using Inclusive Guide, you can join and support organizations such as The Unpopular Black and Black Girls Travel Too that seek to make travel more accessible and fun for specific groups of people traditionally left out of the American travel narrative. In these two examples, Black individuals are being centered when, for far too long, we’ve been excluded from both outdoor spaces and the general notion of “adventure.” There are too many affinity groups and resources to list here (that’s a good thing!), so I encourage you to find a group that speaks to you, but some of the organizations I support are Blackpackers, Fat Girls Hiking, Latino Outdoors, Native Women’s Wilderness, and Muslim Hikers. There’s a space for you no matter what your identity is. In the meantime, check out Inclusive Guide’s social media and blog, as well as all of KWEEN WERK’s channels, to follow me on my Liberation Tour throughout the South and Midwest. We’ll be sharing educational posts and videos related to Black travel over the course of my two-week trip. I also plan on using Inclusive Guide in real time so that you can see and learn about some of the inclusive places I visit. While this trip is ultimately a bonding experience for my family—and some well-deserved R&R for myself—I hope my journey increases the visibility of Black people in outdoor spaces and the world of travel more broadly. We be trippin’, y’all—we always have been. If you’ve been wanting to embark on an adventure but are worried that you won’t belong or that it isn’t for you, let me be the first to say that you 100%, absolutely can. Traveling is for everybody—and we’re taking it back. We’re excited to announce that Inclusive Guide is hosting a signup giveaway! Each week in May, we’ll be randomly selecting a user who signs up to use the Guide and leaves a review of a business. We have some awesome gear from NEMO Equipment to give away—we love their products, and we hope you will, too.

We hope this contest encourages you to engage with the Guide and see what benefits it can provide to both you and businesses. These reviews allow us to collect inclusivity data that we can analyze for businesses to help them become more cognizant of the customers who use their services. This data will also help businesses to take actionable steps toward bolstering their inclusivity efforts. At the same time, your insights will benefit community members as they make decisions about which businesses to patronize. Check out the detailed guidelines below, and be sure to follow the contest as it develops on our social media channels! To Enter: 1. Follow us on social media (@InclusiveGuide), and like the most recent giveaway post. 2. Go to our website, InclusiveGuide.com and click "Create Account" to sign up. (cell number required in order to sign up) 3. Type in the name and city of the business you'd like to leave a review for. (most businesses will be located in Colorado) 4. Click “Leave a Review,” and follow the prompts to share your experience at the business. Official Rules: 1. Eligibility: The Inclusive Guide Giveaway is open to legal residents of the United States who sign up and register at inclusiveguide.com. Entrants must be 21 years or older as of their date of entry in this promotion in order to qualify. This giveaway is subject to federal, state, and local laws and regulations and void where prohibited by law. 2. Agreement to Rules: By entering this giveaway, the Entrant (“You”) agrees to abide by the Sponsor's Official Rules and decisions, which are fully and unconditionally binding in all respects. The Sponsor reserves the right to refuse, withdraw, or disqualify any entry at any time at the Sponsor’s sole discretion. By entering this giveaway, You represent and warrants that You are eligible to participate based on eligibility requirements explained in the Official Rules. You also agree to accept the decisions of the Sponsor as final and binding as it relates to the content of this giveaway. 3. Entry Period: This promotion begins on May 2, 2022 and ends on December, 31, 2022. To be eligible for the giveaway, entries must be received within the specified Entry Period. 4. How to Enter: Eligible entrants can enter the giveaway by registering on inclusiveguide.com and writing a business review, your entry must fully meet all giveaway requirements, as specified in the Official Rules, in order to be eligible to win a prize. Incomplete entries or those that do not adhere to the Official Rules or specifications will be disqualified at the Sponsor's sole discretion. 5. Prizes: The Winner(s) of the giveaway will receive various prices provided by Nemo Equipment and other partners to be named later. The actual/appraised prize value may differ at the time the prize is awarded. The prize(s) shall be determined solely by Inclusive Guide. There shall be no cash or other prize substitution permitted except at the Sponsor’s discretion. The prize is non-transferable. The prize is non-transferable. The Winner, upon acceptance of the prize, is solely responsible for all expenses related to the prize, including without limitation any and all local, state, and federal taxes. 6. Terms & Conditions: In its sole discretion, Inclusive Guide reserves the right to modify, suspend, cancel, or terminate the giveaway should non-authorized human intervention, a bug or virus, fraud, or other causes beyond the Sponsor’s control, impact or corrupt the security, fairness, proper conduct, or administration of the giveaway. The Sponsor, in the event of any of the above issues, may determine the Winner based on all eligible entries received prior to and/or after (if appropriate) the action taken by the Sponsor. 7. Limitation of Liability: Your entry into this giveaway constitutes Your agreement to release and hold harmless the Sponsor and its subsidiaries, representatives, affiliates, partners, advertising and promotion agencies, successors, agents, assigns, directors, employees, and officers against and from any and all claims, liability, illness, injury, death, litigation, loss, or damages that may occur, directly or indirectly from participation in the giveaway and/or the 1) Winner accepting, possessing, using, or misusing of any awarded prize or any portion thereof; 2) any type of technical failure; 3) the unavailability or inaccessibility of any transmissions, phone, or Internet service; 4) unauthorized intervention in any part of the entry process or the Promotion; 5) electronic error or human error in the Promotion administration or the processing of entries. If you think about the word “nature,” you might conjure images of wilderness areas—the undeveloped stretches of valleys and mountains that exist across the American West, for example. More specifically, you might picture Yellowstone National Park or the famous black-and-white photos of trees, lakes, and cliffs taken by American photographer Ansel Adams. All these mental images certainly are natural, but they only represent a fraction of what nature is. As Emma Marris says in her 2016 TED Talk titled “Nature is everywhere — we just need to learn to see it” in Banff, Alberta, “Nature is anywhere where life thrives.” We at Inclusive Guide wholeheartedly agree with this more expansive definition. Romantic ideas of a pure, untouched nature discourage those within historically disenfranchised communities from connecting with the natural world. When we consider nature solely as the faraway trails, forests, rivers, and slopes that reaffirm our culture’s dominant view of the outdoors, we ultimately exclude the folks who can’t take time off to roadtrip to a national park, who can’t afford x gear or y equipment, or who are made to feel unwelcome and unsafe in certain natural environments. It’s no secret that there’s a “nature gap”—also called the “adventure gap”—in outdoor recreation, as the majority of Americans who enjoy these recreational activities are white. Indeed, Census Bureau data shows us that “[w]hite Americans vastly outnumber people of color in outdoor activities like fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching.” This is a problem. How can we fix the nature gap? The first step is redefining our relationship with the natural world. Following Marris’ lead, we must embrace the idea of nature being all around us—and yes, this includes cities and other heavily industrialized spaces. These places are natural because life, including humans but also various plants, insects, and other species, thrive in them. What about the children who live in inner-city New York, Chicago, or Philadelphia who don’t have ready access to mountaintops or waterfalls? Do they not get to enjoy nature? When a kid finds a roly poly under a rock in their front yard, isn’t that engaging with nature?

Parker here. Most of you know me as the co-founder of Inclusive Journeys, the company behind the user review platform Inclusive Guide. I also founded Ecoinclusive, a service that provides diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training and resources to leadership teams at environmental organizations. I’ve spent the past 24 years of my life working in natural resources, environmental education, and outdoor recreation. It’s become my life’s mission to dismantle and reimagine the systems that continue to harm historically disenfranchised individuals, especially in environmental and conservation spaces. And I won’t stop until the world’s a better place for all.

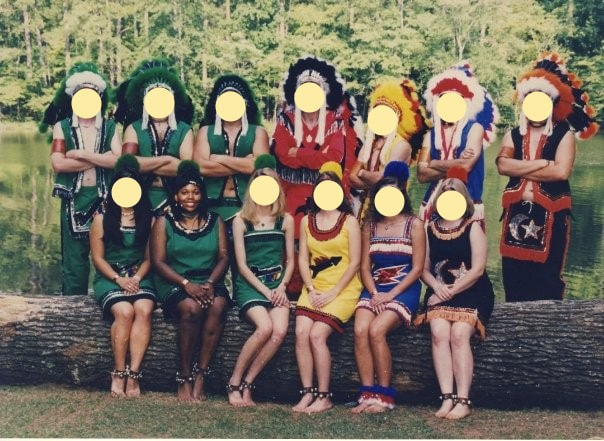

If you know me or have worked with me over the years, some of the stories in this blog post may be uncomfortable or surprising for you, but I’m sharing my experiences to bring light to the fact that there’s much more work to be done. The amount of racism and microaggressions I’ve endured over the course of my career would be truly staggering to some. This admission may also come as a surprise because in some ways, I helped to reinforce and uphold the white supremacist systems I, myself, was a victim of. This article is not a call-out but rather a reflection of my personal growth. You see, there were many times I sheepishly laughed at racist jokes about myself. There were many times I reassured those who perpetrated racism against me that I was okay and didn’t take offense. There were many times I told other people of color that things weren’t so bad. I look back at that version of myself and feel a strange mix of emotions—yes, shame and embarrassment, but also pride and hope because I’ve come so far. Because of my experiences as a Black woman, I’m intimately aware of the harsh realities those at the margins of our society are forced to endure, even when people think racism and sexism are done, ableism is fake, or the fight for queer rights is over. I’ve lost count of the number of times my mixed-race family has been harassed in public, the times I’ve been told that Black people don’t hike or camp, or the times my hair has been policed at the workplace. Though I can’t overlook the “-isms” and systems that harm me and other marginalized communities, it took me a long time to realize the presence of such structural problems in the first place. White supremacy is what the US was founded upon, and people of color are often the recipients of its torment. However, in my past, I subscribed to white supremacist delusion without even knowing it. Even as the target of white supremacist practices, I also upheld this delusion. Nobody is born “woke,” and I—like everyone on this journey—am still in the process of unlearning some of the problematic behaviors our white supremacist society encourages people to engage in. I’m not perfect, but I’ve come a long way. I want you to know that you can change, too, no matter where you’re from or what your background is. This is why I’m sharing my journey with you. A good place to start is around the ages of 18 to 20, when I began my career. In 1997, the first summer camp I worked at as a full-time counselor had a Native American theme. Campers were divided into different tribes: Shawnee, Cherokee, or Muskogee. Throughout the week, children would compete in activities to try to win the coveted “tribal shield,” which was a chest full of pins. The camp’s talent show was held in an auditorium described as the “air-conditioned tepee,” and every week counselors would perform a fake Native American love story during a ceremony called “The Pageant.” I participated, even wearing a feathered headpiece designed for female counselors while the male counselors wore headdresses. I still think about the children I worked with and the harmful stereotypes I helped perpetuate among them. During this time in my life, I was woefully unaware of the previous and ongoing genocide against Native American populations in the US. The camp’s activities not only gave campers an inaccurate representation of Indigenous life and customs; they also helped perpetuate the idea of the “extinct Native American.” These stereotypes disrespect, degrade, mock, and harm Native peoples—in fact, Indigenous individuals experience the highest rate of police killings compared to any other group. I was only able to learn all this in retrospect. Fast-forward to my early 20s. I was now working at an environmental education center in the Midwest. That center had an evening event known as the “Underground Railroad Activity.” You can probably guess what this “game” included, but I’ll expand. Students would pretend to be slaves in a traveling choir accompanying their master. This master, who was a teacher or chaperone leader, carried papers supposedly attesting to the slaves’ right to travel. Throughout the activity, the students would be stopped by various people and were instructed to look down whenever they encountered others and to be silent unless they were spoken to. Students who didn’t follow these instructions were yelled at until they submitted. During this activity I often played the role of another slave who would help the students escape, having to hide at times to avoid being caught. Toward the end of the activity, a lantern would be lit and a quilt hung to signal that the students could enter a safehouse and go downstairs to a basement, where they would wait in a dark room while the local “police” visited the house looking for escaped slaves. The folks upstairs would yell that they knew slaves were hiding in the house, threatening to find them and take them back. This horrific activity concluded with a short discussion that lacked any semblance of depth or nuance. By participating, I was complicit in how this abhorrent activity impacted both the students and myself. That center’s education staff had little background knowledge on the history of the Underground Railroad, let alone slavery, but we facilitated the activity anyway. Further, the historical “context” we provided after the game did little to justify the trauma we inflicted upon our students. It took me years to understand the psychological and emotional impact my participation had on students, as well as on myself. Several years later, I began working at a different environmental education organization. By this point, I’d vowed to myself that I’d never contribute to something like the fake Native American camp or Underground Railroad activity ever again. However, I found myself being challenged in a different way. The director of this new organization would bring her dog to work. The dog noticeably only barked at Black people. As such, she sometimes referred to her pet as her “little KKK dog.” In an effort to explain this behavior, the director said her dog had a “bad experience” with a Black person. One of my colleagues, a Black man from Philadelphia, eventually approached me about the director’s reference. I shrugged and told him that it was okay. “It’s just the South,” I added. In a moment when I should have supported my Black colleague, I excused the director’s actions, minimizing both our experiences. I thought, in a way, that I was “protecting” my colleague. The director’s behavior was reprehensible on many levels, but I was worried about the ramifications of calling out this behavior in a public way. By shrugging off my colleague’s concern, I was actually protecting the director instead. I was protecting her racist, white supremacist ideologies and practices. Although I was aware of these micro/macroaggressions, I still didn’t address them. From housing and infrastructure to education and policymaking, white supremacy is woven into every part of our society. In order to break free of white supremacist delusion, we must first be willing to wake up from it. We have to educate ourselves by reading the literature of civil rights leaders, activists, First Nations, and Indigenous peoples who are skimmed over in our history books. We must seek out intentional affinity groups such as student alliances and nonprofit organizations to build community. Education and community are the foundation upon which one can overcome the internal barriers and fear that often keep us from confronting systemic oppression. This is where my liberation lies, and it continues to set me free every day. Still, education and allyship are only one part of the solution. While remembering our past wrongs is important, it’s also important that we answer these wrongs with vigorous action and change. As a co-founder of an inclusivity-focused business, I do everything I can to empower the marginalized groups I overlooked when I was younger. For example, I invite (and compensate) Native individuals to have a voice at events that I host and to provide invaluable insights about the work I’m doing—and should be doing. I also steer folks in the direction of organizations that are doing similar work and let them know how they can directly support these causes. If you’re a leader, or have any semblance of power in our white supremacist country, you can act now to elevate the perspectives disregarded in key business decisions. We can’t dismantle the systems that continue to harm us if those at the margins of our society have no seat at the table. The reality is that I was both the victim and the perpetrator of white supremacist delusion. Everyone is affected by white supremacy, including white people—regardless of the supposed benefit. Nobody’s perfect. As such, we’re all capable of growth and change. Acknowledging our past transgressions is the first step. This healing is the very reason we created the Inclusive Guide. Everyone is part of the problem, so everyone must be part of the solution. I welcome you to join me on this journey. |